How the American church is grappling in a society that's abandoning God

The Christian Post’s series “Leaving Christianity” explores the reasons why many Americans are rejecting the faith they grew up with. In this eight-part series, we feature testimonies and look at trends, church failures and how Christians can respond to those who are questioning their beliefs. This is part 4. Read parts 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7a, 7b, and 8.

“Do you ever miss being a Christian?”

“No,” replied Anthony B. Pinn comfortably.

The Agnes Cullen Arnold professor of humanities and religion at Rice University in Houston, Texas, then paused before continuing quickly.

“No, because no longer being a Christian doesn’t mean that I’m without ritual, without community, that I’m without relationship or without a sense of awe. I continue to have a sense of awe, but it’s secular. I walk outside and I’m baffled by the beauty. I think about life even from an evolutionary perspective and it creates a sense of awe that we are here,” he told The Christian Post one late September afternoon.

It took him a while to get here but after years of attending church, starting as a child when his mother would take him, then eventually becoming a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Pinn, 55, has found peace in humanism. His life as a believer is over, he said, because he has concluded there is no God.

“I’m one who does not believe, who doesn’t hold to any supernatural claims, no sense of God or gods, no angels or demons, nothing that is supernatural. My thinking is grounded in what material circumstances make available to us. And my primary obligation and responsibility is to the nurturing of life in the context of human history,” he explained.

Pinn’s deconversion in the early 1990s is the result of a “slow build” that wasn’t an “aha! moment.”

“As a college student in New York, I was working at a church in Brooklyn. I entered ministry fairly young. I was an undergraduate working as a minister for youth at Bridge Street AME Church in Brooklyn and so much of what I had assumed and what I had been taught concerning theism, Christian faith in particular, ran contrary to what I was experiencing,” he said.

“I was having an increasingly difficult time lining up my faith stance with world conditions and world need that I seem to be answering questions that people within my church weren’t asking and avoiding the questions that were really of fundamental importance to them. And so I started having some discomfort with my role in Christian ministry.

“My thinking initially was to rethink my theology, rethink ministry. I left Columbia with a B.A. degree in sociology and went to Harvard Divinity School and these issues continued for me. I had a difficult time reconciling my faith with human need,” Pinn said.

“What can you say about God in light of human suffering in the world? And that was becoming increasingly difficult for me to develop a positive word about God in light of human misery. The misery surrounding my church and my church family."

After pursuing graduate studies in religion at Harvard University in search of answers, Pinn felt compelled to make a decision.

“I decided that I really didn’t believe in God anymore. I wasn’t a Christian. I wasn’t even a theist anymore. And so I contacted the minister at the church where I’d been working, indicating I would not be returning. I contacted my church officials and indicated I wanted to surrender my ordination and I left the church and left theism,” he said.

Pinn didn’t wait to see the reaction from his church, neither did he care to know what the leaders thought of his decision.

Like Pinn, millions of Americans who were once committed Christians have continued to increasingly disengage with their religion in recent decades, and churches have been struggling with the culture shift in which there are no absolute answers.

A new study from the Pew Research Center noted in October that only 65 percent of Americans now identify as Christian while those who identify as religiously unaffiliated — a group which includes atheists, agnostics and people who don’t identify with any religion — swelled to 26 percent of the population. The drop in the number of Americans identifying as Christian reflected a 12 percent decline when compared to the general population 10 years ago. The decline was visible across multiple demographics but particularly among young adults.

Research by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2016 on why Americans are leaving religion also pointed to the increasing share of American adults who have been joining the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated, and said it is being “fed by an exodus of those who grew up with a religious identity.” Younger Americans today are also more likely than seniors to be raised without a religious identity.

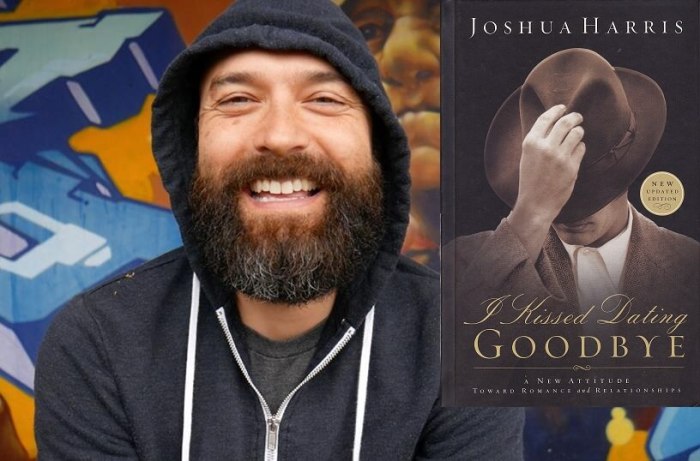

The conversation about this growing concern emerged as a major talking point this summer when Joshua Harris, former lead pastor of Covenant Life Church, the founding church of Sovereign Grace Ministries in Gaithersburg, Maryland, and author of the Christian cult classic I Kissed Dating Goodbye, announced he was abandoning Christianity and ending his marriage. The conversation grew even louder when Marty Sampson, a well-known Christian worship music writer who has penned lyrics for Hillsong Worship, and Hillsong United, announced his faith was on “incredibly shaky ground.”

Covenant Life Interim Senior Pastor Kevin Rogers wrote in a letter to his congregation in the wake of Harris’ announcement that while it was difficult to handle, the Bible had a response for Christians falling away.

“This news isn’t just a lot to process theoretically. It hits home personally,” Rogers said, assuring his members that Harris’ apostasy was not something unfamiliar to the faith.

“Several times Paul mentions former Christian leaders ‘swerving from,’ ‘wandering from,’ or ‘making shipwreck’ of their faith. So while this is sad and confusing, it isn’t new,” Rogers explained. “Paul says some had gone off course theologically. Others behaved in ways that violated Christian conscience. For others, it was greed. In every case, Paul’s hope was for redemption and restoration. That these leaders would develop ‘love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith.’ (1 Tim 1:5) That should be our hope and prayer for Josh as well.”

Commenting on his new life in a recent post on Instagram, Harris appeared to criticize his former Christian worldview as alienating to people who did not share his beliefs. He now expresses a desire to love and accept everyone even if they disagree.

“This is how I want to love people. It’s new for me. For so many years I embraced the opposite mentality. Of course I claimed to love everyone, but the reality is that I held people who thought differently about doctrine and Christian standards at arms length. I viewed them with suspicion at best, with contempt at worst,” he said.

“Looking back I see now how often my tribe of Christians labeled and categorized people. It seems we label ‘the other’ to write them off. To dehumanize. To excuse a lack of love. There’s still so much I’m unpacking about what shaped and motivated this way of living. But I think at the root of it was fear and pride. Fear of being uncertain. Fear of wrestling with new ideas. Pride that finds security, not necessarily in God or truth, but in being better than, different than, separate from other humans. I don’t want the so-called safety found in separateness anymore. There’s a place for you and me at the table.”

Earlier this year, in a letter to his congregants, the Rev. David H. Locklair, leader of Hope Lutheran Church in Portage, Indiana, worried publicly about the possible demise of his denomination and the struggles of his specific church in his annual report due to shrinking numbers and a lack of support.

“A few years ago, I read a report that predicted that the Evangelical Lutheran Synod, our church body, would not exist twenty years in the future. The reasons for such a dire prediction were shrinking membership and shrinking offerings. How can you have a church body without people and gifts to keep it running?” he asked.

“In 2018, Hope Evangelical Lutheran Church had an average attendance of 32. Our attendance numbers are trending downward over the years. In 2018, Hope was able to pay all its bills but we do not have a great surplus of funds in the bank. Our offerings too are on a downward trend over the years. Will Hope be able to pay its bills, maintain its building, and support full time ministry into the future? What do we need in order to be sustainable?”

His answer to his small congregation was: “This new year and into the future, take to heart the words of Hebrews 10:24-25: ‘And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near.’"

A postmodern world

Mark R. Teasdale, E. Stanley Jones associate professor of evangelism at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois, noted in an earlier interview with CP that a search for meaning in a postmodern culture appears to be challenging some believers to abandon deeply held beliefs about God and moving them away from traditional congregations.

"Before the time when evangelicalism arose, the focus was in making certain that we had absolutes. So the belief of modernity was the belief that there are absolutes. Everyone could have access to those absolutes if they simply use their reason appropriately and that those absolutes would hold no matter what situation you're in," Teasdale said.

"What happens in postmodernity is that the idea of absolutes become far less important. Instead, we're looking at a time when narrative story becomes much more important. And so people are looking for something meaningful, a meaningful story to make sense of their lives.

"And it doesn't really matter much whether it's 'true' in the sense that it fits with an absolute truth that's out there somewhere. What matters is that it's meaningful for you and that's really what's important."

Colin E. McNamara, a staff attorney at the American Humanist Association, who completely abandoned Christianity at age 20, agrees. And he thinks it’s a good thing for Christianity.

“There have been people who reject the notion of God since ancient times, but for a lot of human history it wasn’t safe to say as much out loud. As we’ve slowly and painfully developed into a more open and accepting society, I think more and more people are willing to publicly profess their atheism without fear of becoming a social pariah," McNamara said.

"I believe that this has had a kind of snowball effect: the more people ‘come out’ as atheist or nonreligious, the more likely that those who were previously too afraid to speak up will do so, and there will be a larger community of people — both fellow nonbelievers and tolerant believers — who will welcome them with open arms,” he told CP.

“I can understand how Christians might be unnerved by this trend, but I really don’t think they should be. Ask yourself: Do you want sincere Christians or fake Christians? If we foster an open and accepting society where people feel free to express their true thoughts and feelings, you’re more likely to get more of the former and less of the latter. That’s a good thing, right?”

In a recent analysis of data from the General Social Survey of five-year windows in which individuals were born spanning from 1965 to 1984 and published by the Barna Group, Ryan Burge, an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and pastor of First Baptist Church of Mt. Vernon, Illinois, highlighted how the sustainability of the church is also being challenged by the trend that shows generations raised in the church are also not typically returning to church when compared with members of the “Baby boomer” generation born between 1945 and 1964.

“Many pastors are standing at the pulpit on Sunday morning and seeing fewer and fewer of their former youth group members returning to the pews when they move into their late-20s and early-30s. No church should assume that this crucial part of the population is going to return to active membership as their parents once did,” he explained.

“The data is speaking a clear message: the assumptions that undergirded church growth from two decades ago no longer apply. If churches are sitting back and just waiting for all their young people to flood back in as they move into their 30s, they are likely in for a rude awakening. Inaction now could be creating a church that does not have a strong future.”

The impact of race on faith in God

Some studies, such as a 2014 Pew report that shows marked disparities in faith in God by racial group, does not reflect a clear picture of who really believes, Pinn believes.

“According to Pew, a vast majority of African Americans claim belief in God, but I don’t know that that is synonymous with religion. One could also say these folks are spiritual, whatever that means. What Pew tells us is rather limited and we tend to build out from that. We know that a significant percentage of the black population believes there is a God, but the number decreases if you ask, ‘How many of you go to church regularly,’” Pinn explained.

The results of that study showed that blacks, as a racial group, have the highest percentage of members with “absolutely certain” belief in God at 83 percent; Asians have the lowest at 44 percent. Among whites, 61 percent, while Latinos stood at 59 percent.

When it comes to the church and the black community, however, Pinn argued that the relationship is more than just about faith.

“The black church has never simply been about spiritual development. The black church has always tried to position itself as an organization that has met a full range of needs. And so folks go for this greater range of needs,” Pinn said.

“I’ll give you one example of this. After the Civil Rights Movement, church involvement decreases, and that’s not just black denominations. Overall, church involvement in the United States, black and white church involvement, decreases after the Civil Rights Movement.

“Now, in black churches, it begins to experience an uptick in the 1980s, but these black folks are also folks who played by the rules. They were told after the Civil Rights Movement, go to the right schools, live in the right neighborhoods, use English in a particular way. Play the game and you will be successful. But they continue to hit racism,” Pinn said.

“And here’s the catch — they have surrendered so much by cultural connection, they have surrendered social identity. And for lots of these folks, particularly black middle class, going back to church provided a way to connect culturally, to connect socially, to network in terms of economics. And it was a space in which black folks didn’t have to explain why they were angry."

“And so, you had a lot of black folks who went back to church for those more secular reasons. … And if the sermon preached was the price they paid, this was the price well-worth paying. That is to say, I am not convinced that all these folks in black churches believe the faith in the same way. For some, it’s a much more pragmatic move. This connects me to black people. It connects my children to black people, and with a lower price tag than Jack and Jill,” he said.

Pinn further argued that when it comes to millennials and the black church, the relationship is being upended by social activism.

“You experience now a decrease in participation from millennials, for example, because these religious organizations are not meeting their needs. They’re not answering the questions that matter to these folks. But also, so many of these churches have positions concerning people that millennials are finding objectionable — that a significant percentage of millennials are socially active. They are concerned with issues of justice …,” he said.

How better discipling can keep people faithful

Dale Partridge, a pastor and house church planter and founder of Relearn Church — a group of pastors, church planters and theologians who want to “unlearn what culture has taught us about church and relearn how the Bible instructs Christians to gather” — believes another reason Christians are leaving church is because the structure of the church, in practice, is wrong.

“Millions of Christians are leaving the institutional church on a search for Jesus,” his website says.

“What’s happening today is that most pastors aren’t pastors. They are Bible teachers. They are evangelists. They’re not pastors. Most people don’t even know what a pastor is. They’ve never even experienced a pastor. They’ve never been discipled. They’ve been taught but they’ve never been discipled,” he told CP.

“There is no relationship, and so pastoral care, I would say, it’s important that pastors have relationship to stay healthy even for his own health. These pastors of these churches are getting buried under the weight of performance. All they’re hearing is the bad news. They have no connection with anybody because they are afraid to be known, and [there's] so much to lose if anything goes sideways.

“It’s an isolating place. It’s always on guard, checking yourself. You can’t ever be who you really are. I think what most pastors want is they want what Jesus had. They want the crowd and then they want the 12.”

Much of the biblical ideas on how church should be practiced, he said, cannot be effectively implemented in the current church model that exists today.

“These ideas — pray for one another, confess your sins to one another — you cannot do that with a stranger. ... And we’re just in a whole mess with the size of the church," Partridge argued. "When you talk about one thing you have to talk about everything. I’d say it all leads back to this very isolating and very incorrect experience for the pastoral life. It’s kind of like Moses prior to Jethro saying, hey, you need to break everybody up into groups here. It’s unsustainable what you’re doing here."

He said many large churches have been trying to fix the problem by implementing small groups but a small group isn’t really a church by biblical standards. A church, he noted, has to include things like communion, eldership, governance and gender roles that are “critical in Scripture.”

More and more leaders have been coming to him for help with converting traditional churches into house churches, and he believes house churches are the answer to the current crisis of faith.

“I think a lot of people know, Christians, godly men, that we are coming to a time, depending on this election, say five to 15 years from now, we are coming to a time that we will no longer be able to gather the way we gather now without compromising Scripture. It’s coming,” he said.

“I felt like the Lord was saying, Dale, prepare a place for my sheep that they can go when they can no longer be in the pastures that they are in now. That’s what we’re doing. We’re preparing a way,” he said, comparing his efforts at Relearn Church to Noah’s Ark.

Is secularization really a problem?

When asked if he felt the increased secularization of American culture was having an impact on the growing Christian apostasy, Pinn pointed to the influence of politics instead.

“Well, no. I wouldn’t say the secularization of culture. I think these more recent episodes are a consequence of the church selling itself on behalf of [President Donald] Trump. That, it seems to me, these folks are responding to a historical moment that has to do with so many Christian communities embracing the toxic behavior and conversation of Trump and people saying enough of this. Not the growing secularization,” Pinn argued.

He further noted that there are some members of the Christian community who would like to leave but can’t because they would lose too much.

“It takes a lot to leave ministry. You have those who are leaving, but it seems to me you also have those who don’t believe but maintain their church affiliations. They just go through the motion because there’s just so much to lose," he said.

"If you’re involved in church ministry and you decide, ‘I just don’t believe anymore’ and you leave, what do you do? You spent your life crafting a particular set of tools, what do you do? Who’s your community? So I think a lot of folks, rather than facing that kind of terror would just stick it out and go along for the ride, not really buying what’s being preached but seeing of value some of the other elements of church life community."

For Partridge, he believes that, like many other Christians who have abandoned their faith, high-profile ex-Christians like Joshua Harris are rejecting the institution of church instead of God.

“He just saw the man-made mess of the church over and over. He just saw the commoditized, industrialized, politicized version of the church over and over and what did he do? He said, ‘God this is all fake.’ He blames God for the works of man. And it’s like yeah, it is fake. It’s not right."

"If you went to China and you went to Afghanistan and you saw the families that are baptizing themselves inside of twin bed mattress frames that are stapled together with rubber liners, crying and being persecuted and still loving the Lord and teaching in faithfulness, you’d love the Lord again,” he said, “because you’d see the supernatural transformative power of the cross. But they don’t see the Lord because He’s not there, just man. … He’s not there in the same way that the Scriptures prescribe Him to be there.”