Outcomes and entanglements: Quantum science can reveal spiritual truth (part 1)

Quantum science will get us as close to understanding God as natural science can ever take us. In fact, certain discoveries and implications of quantum theory describe on the material level what the Bible reveals on the spiritual.

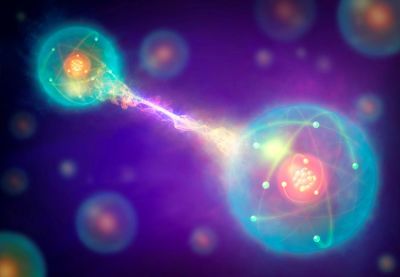

Quantum entanglement is a stunning example showing how discoveries in natural science and revealed spiritual truth often parallel and even complement one another.

Though I make no pretense of being a natural scientist — let alone a physicist — I will now dare write about the correspondences of spiritual and material science: specifically, quantum theory and the intersection with theology.

If scientists can write about theology, surely, I can scribble some lines about natural science. No doubt at some points I will make a fool of myself just as occasionally some scientists and would-be theologians have of themselves.

My scientific credentials reach back seventy-one years to fifth grade when I got curious about the universe. Later, in college, I studied science 101 where, among other things, I learned about the circulatory system of the shark. I confess that I love science and in recent years have turned to deeper studies at YouTube and other purveyors of fascinating things.

I have literally walked through the courtyards of Harvard, Cambridge, and Oxford, and listened and watched as the greatest contemporary scientists from all elucidated quantum mechanics. I have read books by some of the great names in popularized physics, including Brian Greene and his fascinating book on string theory, The Elegant Universe. I have also driven the entire length of the Texas A&M campus and hopefully soaked up some of the technical energy quanta floating in the air around that noble institution.

I am aware that Einstein was offended by quantum theory and called quantum phenomena “spooky action at a distance.” He also declared with respect to creation, that God would not “play dice.”

My theological credentials go all the way back to 1955 or so in Sunday School. However, I pursued theological formal studies at Samford University, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Trinity Theological Seminary, and, informally, at my childhood home church and Preacher Williams’ seminary of the pew, the hardest school I attended (forgive the pun).

In the 1960s and 70s, I was a budding crusader as a newspaper reporter and editor covering the cultural, social, and religious upheaval of that era. I interviewed people like renegade California Episcopal Bishop James Pike, and “God is Dead” proponent Thomas Altizer. Major liberal scholars were heralding the emergence of a new secularized Christianity, and I began to wonder if it is possible to be an atheist, that is, to make a categorical and absolute statement, “There is no God.” For me — thank God — I found it philosophically impossible and illogical to be an atheist. I recognized that it is a perilous thing to say that “something” does not exist, because to declare it non-existent would mean that I had to have all knowledge of all things lest the “something” might exist in my ignorance gap. It was at that point that I ran into the famous conclusion of 18th-century French philosopher and mathematics genius, Blaise Pascal. His theological view is called “Pascal’s Wager”: “If God exists and I believe in God, I’ll go to Heaven, which is infinitely good. If God exists and I don’t believe in God, I may go to Hell, and that’s infinitely bad. If God does not exist, then whether I believe in God or not whatever gain, or loss would be finite. So, I should believe in God.”

Decades later I would happen upon what would be the clincher showing atheism to be illogical, and even absurd. I discovered this profound fact while doing research for my book Who Will Rule the Coming ‘gods'? that investigates “the looming spiritual crisis of artificial intelligence.” The quote was from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) professor Dr. Seth Lloyd. He pointed out that the universe is a vast quantum computer. It occurred to me that the quanta, or information, must already be present. That is, the computer does not create the basic information, but the machine is made to respond to and process the information already there. Again, the Information was already in existence before the Big Bang and is the reason information-based creation occurred.

This fact was stunning in its theological implications. Information is a product of mind, and mind is an attribute of person; therefore, the Person must pre-exist the information. Thus, the Apostle John writes: “In the beginning (already) was the Word (Logos) and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by Him, and without Him was not anything made that was made” (John 1:1-2).

Not bad for a backwater country boy in the First Century A.D.

Science, then, begins with theology. C.S. Lewis puts it this way: “Men became scientific because they expected law in nature, and they expected law in nature because they believed in a Legislator.”

Those early developers of science had no doubt read Romans 1, which reveals that God is made known in the Scriptures, in the incarnation of Christ, and through what is made … nature, His creation.

Quanta — packets of energized information — constitute the particles that makeup everything that exists. But one of the most fascinating and theologically mesmerizing features of quantum mechanics is “entanglement.” This occurs when two particles relate to one another in such intensity that what happens to one happens to the other, even if they are galaxies apart.

We will dig down into the theological implications of entanglement in the next two parts of this series.

Wallace B. Henley is a former pastor, daily newspaper editor, White House and Congressional aide. He served 18 years as a teaching pastor at Houston's Second Baptist Church. Henley is author or co-author of more than 25 books, including God and Churchill, co-authored with Sir Winston Churchill's great grandson, Jonathan Sandys. Henley's latest book is Who will rule the coming 'gods'? The looming spiritual crisis of artificial intelligence.