Creating a Consistent Interpretation of Jesus' Teachings

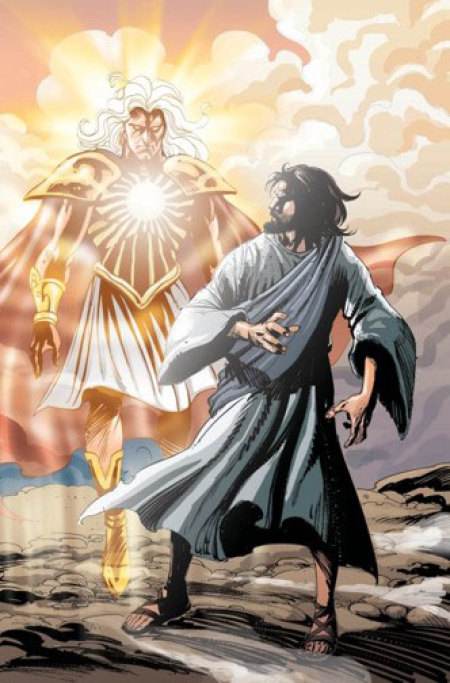

Copan's Argument. In Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG) and Cross Vision (CV) I argue that the violent depictions of God in the OT are incompatible with the non-violent, self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing God who is fully revealed in the crucified Christ. It's my contention that we therefore need to interpret these violent divine portraits, as well as the rest of Scripture, through the lens of the cross. And it is only when we interpret these portraits in this way that we can discern how they bear witness to the crucified Christ, as all Scripture is ultimately supposed to do (Jn 5:39-47; Lk 24:44-47; I Cor 15:3).

Paul Copan doesn't disclose an alternative way of understanding how the OT's violent portraits of God bear witness to the cross, but he is nevertheless confident that my proposed way of disclosing this is misguided. Indeed, he is opposed to any suggestion that the violent portraits of God in the OT need to be reinterpreted at all. In his view, these portraits are not incompatible with what we learn about God from Jesus and the NT. To establish this point, Copan highlights passages in the NT that he believes depict God in violent ways or that otherwise condone violence, as we have seen over the last several posts.

Arguing along these lines, Copan notes that I understand Hosea's depiction of Yahweh vowing to "cut [Israel] to pieces" to be a reflection of Hosea's "fallen and culturally conditioned heart" and mind (CWG, 798-99). If this is correct, Copan suggests, then I must accept that Jesus also had a fallen and culturally conditioned heart and mind, for he argues that "Jesus uses identical language." He writes that in Jesus' teachings,

God is a "severe" master (Lk 19:21-22, 46), an angry landowner (21:33) who will "bring those wretches to a wretched end" (Lk 21:41; cf. "kill" in Lk 20:16), and will "cut them in pieces" (Mt 24:51

These passages are found in three parables of Jesus: the parable of a master and a wicked servant (Mt 24:45-51; Lk 12:42-46), the parable of ten pounds that was given to three servants of a wealthy landowner when he went away on a long journey (Lk 19:11-27), and the parable of an owner of a vineyard who acquired hostile tenants (Matthew 21:33-41; Lk 20:9-16). I will respond to the first two of these parables in this post, and the last in the subsequent post.

A Preliminary Word. Before I address these parables, however, I think it worth pointing out that the depiction of Yahweh vowing "to cut [Israel] to pieces" was just a small part of what I said reflected Hosea's "fallen and culturally conditioned heart and mind." I was also referring to Hosea's depiction of Yahweh as an enraged husband who was going to drag his wife [Israel] into the desert and have her die of thirst after ripping off her clothes so other men could see her "lewdness" (Hos 2:3, 9-10). I was referring as well to Hosea's depiction of Yahweh as "a lion" who was going to "rip apart" Israel and "devour them" (Hos 13:7-8). And I was referring to Hosea's depiction of Yahweh declaring he "no longer loved [Israel" but instead "hated them" (Hos 9:15) as well as his depiction of Yahweh vowing to "send fire on their cities" (8:14), "slay their cherished offspring" (9:16, c. v.12), and to have "their pregnant women ripped open" and "their little ones...dashed to the ground" (13:16, CWG 798-99).

If Copan is going to stand by his claim that Jesus has the same conception of God as Hosea, he must accept that Jesus could have said all these things. Indeed, since Jesus is God Incarnate, he must accept that Jesus himself did all these things. I, for one, have a hard time imagining Jesus ripping open the wombs of young pregnant women in a fit of rage and smashing their unborn children on the ground.

Searching for a Consistent Interpretation. Still, if Jesus meant to depict God cutting people to pieces in the passages Copan cites, then we must concede that Jesus' revelation of God is not altogether loving and non-violent. But this concession would also create a tremendous problem for us, for now we would have to reconcile these violent depictions of God with the cross. Jesus chose to die out of love for his enemies and at the hand of his enemies rather than to use the power available to him to crush his enemies, and in CWG I spend 87 pages (141-228) demonstrating that the NT regards Jesus' self-sacrificial death to be the fullest revelation of God's eternal character. For example, on the basis of the cross, John concludes that "God is love" (I Jn 4:8) and he defines the kind of "love" God is, and the kind of love God's people are to consistently demonstrate, by pointing us to the cross (I Jn 3:16, cf. Eph 5:1-2).

We would also have to reconcile Jesus' alleged violent images of God with the teachings of Jesus that God is altogether loving and non-violent. For example, Jesus teaches us that we are to love indiscriminately – like the rain falls and like the sun shines — because this is how our heavenly Father loves. Consistent with this, Jesus teaches that our ability and willingness to love and bless our enemies is the central criteria for being considered "children of your Father in heaven" (Mt 5:44-45).

In this light, I submit that if there is a way of interpreting the passages Copan cites that is consistent with Jesus' example and teachings that reveal a completely loving and non-violent God, it ought to be preferred over Copan's violent interpretation of these passages. And as it turns out, this is not at all hard to do, for all the passages Copan cites are parables, and once we understand the nature of parables, we'll see that these parables are not intended to teach that God ever cuts people to pieces. [1]

The Nature of Parables. There are three things we need to know about parables if we are to interpret them correctly. First, there is an "is" and "is not" quality to all parables, and the key to correctly discerning the point of any parable is to correctly apply this distinction.[2] For example, in Jesus' parable about the persistent widow and the unjust judge (Lk 18:1-8), everything depends on our understanding that the point is to teach us to pray like a desperate and persistent widow, not to teach us that God is an unjust judge. So too, in the parable of the dishonest manager (Lk 16:19), everything depends on our understanding that the point is to teach us to make preparations so we will be "welcomed into eternal dwellings" (v. 9), not to teach us that God is like the "master" in this parable who "commended the dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly" (v.8), and thus not to teach us that we should behave like this dishonest manager.

Second, parables typically set up the point they are intended to make by telling stories based on things the audience is familiar with, including, quite frequently, the brutal and often unjust behavior of wealthy and powerful people towards Jewish peasantry. Yet, by using brutal and unjust characters as props, Jesus was not thereby condoning this brutal and/or unjust behavior, let alone teaching that this is how God behaves. To the contrary, the peasant audiences who heard these parables deplored the political system that allowed wealthy and powerful people to rule and abuse them. Some scholars even discern a subtle critique of this unjust system in Jesus' parables, claiming they function a bit like a "political cartoon."[3]

The parable of a wicked servant. Third, while building on harsh realities that were familiar to his audience, Jesus' parables often incorporated absurd elements intended to shock his audience.[4] For example, in Matthew's parable of the master and his wicked servant (Matt 24:44-51; Lk 12:42-46), the servant abused his fellow servants and got drunk with drunkards while the master was away. So, Jesus says, when the master returns, he "will cut him to pieces and assign him a place with the hypocrites..." (vs.51). Not only is the master's punishment shockingly disproportionate to the crime, but the image of this master assigning his servant a "place among the hypocrites" after he had already "cut him to pieces" is intentionally ludicrous.

While the familiar realities assumed in a parable are typically used to set up the point of the parable, its intended lessons are typically found in these shocking and absurd elements. Similar to the way the punch line of a joke functions, the surprise was intended to help impress the lesson of the parable on people's imagination.

In the parable we're discussing, the lesson is that people should not forget that there are consequences for their actions when the "master" is away, and the absurd way this point is expressed makes the lesson memorable. But the familiar image of a master who went away for a long time and who was ridiculously vindictive in his punishment once he returned is simply a prop used to set up this punchline. The point of the parable, in short, is about how we should act, not about how God acts when he judges us.

In this light, Copan is mistaken in claiming that Jesus taught that God will cut people into pieces, similar to the way Hosea (mis)represented God.

The Parable of the Ten Pounds. The same holds true of Luke's parable of ten pounds. A wealthy landowner entrusted this amount (worth about three months wages) to each of his three servants, instructing them to make a profit while he went away to make himself king over some people in a distant country, despite the fact that these people hated him and didn't want them to be their king (Lk 19:11-27). One servant made ten more pounds for his master, so he was put "in charge of ten cities," while a second produced five more pounds for his master, so he was put "in charge of five cites." But the third servant was afraid, for he knew his master was "a hard man, taking out what [he] did not put in, and reaping what [he] did not sow." This servant therefore tucked the ten pounds "away in a piece of cloth."

The master rebuked the servant for earning no interest for him and he gave the ten pounds this servant had been given to the most prosperous servant who had already been put in charge of ten cities, for "to everyone who has, more will be given, but as for the one who has nothing, even what they have will be taken away." This master then ordered some servants to go capture "those enemies of mine who did not want me to be king over them," telling these servants to "bring them here and kill them in front of me.'"

The point of this parable is not (thankfully!) to teach us that God is like this ruthless, unjust, and power-hungry landlord. This man rather represents the kind of ruthless and greedy person "of noble birth" that his audience was all-too-familiar with, and he simply serves as a prop for the punchline of this parable. The punchline is that if we are faithful with the little that has been entrusted to us, more will be entrusted to us, but if we are fearful instead of faithful, we will lose even the little that was entrusted to us.

As is typical of Jesus' parables, this point is expressed in shockingly absurd ways. While we can easily understand how more can be given "to everyone who has," it is absurd to say that, "for the one who has nothing, even what they have will be taken away." You can't take something from "one who has nothing"!

Similarly, the suggestion that a landowner would or could put a servant in charge of five or ten cities, let alone do so simply because a servant had earned him an extra five or ten pounds, would have struck Jesus' original audience as comically ludicrous. But arguably the most absurd aspect of this parable is Jesus' depiction of this newly enthroned king of a distant country having his new subjects brought to him en masse so he could watch them all be slaughtered "in front of [him]." This is both a "political cartoon" about the political realities Jewish peasants suffered at the hands of powerful tyrants and a very memorable lesson about the importance of being faithful. But, contra Copan, it is most definitely not a parable about what our heavenly father is like.

NOTES:

[1] For a more comprehensive treatment, see D. J. Neville, A Peaceable Hope: Contesting Violent Eschatology in New Testament Narratives (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013).

[2] B. E. Reid, "Violent Endings in Matthew's Parables and Christian Nonviolence," CBQ 66 (2004) 237-66 (254)

[3] See e.g. Carter, "Construction of Violence"; Myers, Enns, Ambassadors of Reconciliation, 76-7; Herzog II, Parables as Subversive Speech.135-9.

[4] K.R. Snodgrass, Stories With Intent: A Comprehensive Guide to the Parables of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans,2008), 28, 71.

Best-selling author, teacher, and theologian Greg Boyd is leader of Reknew, a website that invites believers and skeptics alike to ask tough questions and consider a renewed picture of God and of his kingdom. Find out more at http://reknew.org