The Song of Songs as tonic for religious abuse : A review of Aimee Byrd’s ‘The Hope In Our Scars’

In the fall of 2019, The Christian Post published an in-depth article series called “Leaving Christianity” and it was, in my view, some of the most illuminating and sobering reporting we’ve ever done.

As a lowercase-o orthodox Evangelical Christian news publication, we had a journalistic obligation to examine an emerging societal trend, irrespective of how we personally felt about it. The series was in part inspired by the documented demographic rise of religious “nones” — those who no longer identify with any religious tradition. And it’s fair to say that a sizable number of these “nones” are disaffected former Christians, known as “exvangelicals,” who now say they have abandoned their faith.

Not long after I started researching for this series, I began to see with greater clarity that behind all the religious identification survey data were real people, and many of them were deeply wounded. Some of them, while not “nones”, were still doing their best to cling to Christ amid what some call “church hurt” — a woefully inadequate phrase, in my opinion, for the injuries and bruises to the soul caused by people who purport to represent Christ.

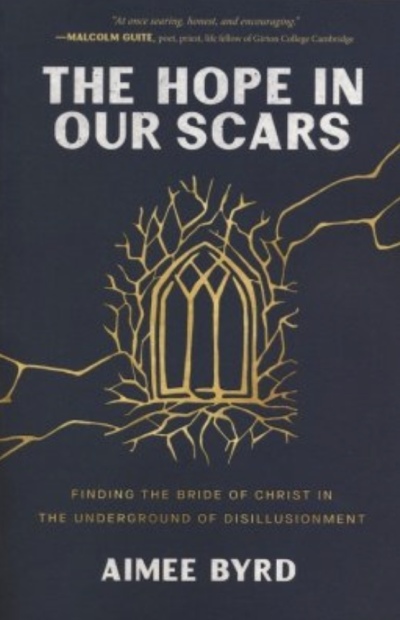

Those 2019 memories resurfaced while reading Aimee Byrd’s latest work, The Hope in Our Scars: Finding The Bride of Christ in the Underground of Disillusionment, which is perhaps best described as one part poignant memoir navigating the cruelty of spiritual abuse within a church, another part finding refuge in the Song of Songs while examining its treasures. It’s also an honest glimpse into Byrd’s diary as she details how she discovered the wonder of what she calls the “underground” of the church-wounded. Written with good-humored frankness, she realized how she and other Christians never thought they would face spiritual disillusionment until after one is put through the proverbial wringer in a church or ministry setting. But the author, though still on a journey of recovery, is neither bitter nor cynical.

When she encountered a pervasive, foul chauvinism (I will not dignify the ugliness by repeating it in this column, see screenshots for evidence) from church officers in her former denomination and then an ineffective ecclesiastical system of church governance to address it, the only place she could go was the “holy of holies” of Scripture, the Song of Songs.

Often waxing poetic and marked with her characteristic knack for delving deep into the intricacies of Scripture one might miss with only a cursory reading of the text, Byrd unpacks for readers how the Song is a balm for those who’ve been scarred. There’s a real, living hope to be found in it. One can rise from disillusionment; the wounded needn’t stay jaded and jilted. Jesus himself is beckoning them to emerge from the shadows.

Throughout the book she emphasizes, lest any of us forget, how the Son of God is more committed to his Bride than any of us could ever be and when He comes back for her, she will be, as the Apostle Paul notes in Ephesians 5:27, without blemish or wrinkle.

In the interest of deepening my understanding, I read the entire Song of Songs several times concurrently alongside Byrd's book. Its sensuous language right from the start made me realize afresh how uncomfortable it is for me, a man, to think of myself as the Beloved. Men, too, are part of the Bride of Christ. Women don’t have these particular mental hurdles and it’s why I believe we need to value their insights.

Erudite theologians have debated for centuries how the Song should be interpreted. Some say it should be read symbolically, with the Song as an allegory for Christ’s immeasurable love for his Bride, the Church. Others maintain it simply extols and celebrates eros, human love, and sexuality as the wondrous things they are. Yet others assert this layered and mysterious Hebrew poetry is something of both.

But it’s good to take a step back to pause and consider the weighty wonder of a book of the Bible that begins with a woman saying: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth.” As Byrd and others can attest, those opening words hit differently for those who’ve been wounded in a church.

Near the end of The Hope In Our Scars, the author references Saint Theresa of Ávila, a 16th-century Carmelite nun who was the first woman to ever be named Doctor of the Church and was known for her meditations on the Song. Those who prefer to avoid its unmistakably intimate opening language and reimagine it to be said in a different style reveal a certain human dullness, St. Theresa wrote, and it indicates a tendency "to create fears and give opinions that manifest the small degree of love of God we have."

For those who’ve been through any kind of abuse in a religious setting, an intense cognitive dissonance ensues when the church or ministry appears to be, at least on paper, doctrinally solid. How is it that a church that is in many ways good, biblically rooted, and where the Holy Spirit is clearly at work simultaneously a source of anguish? Where is this elusive love of God in the place that is supposed to be his holy habitation? And since the abuse they have endured co-opts Him into the violation, it is that much harder, spiritually speaking, to make sense of it.

When asked what she would say to Church leaders who want to understand the phenomenon of the walking wounded, who they are, and how to address it with the wisdom the moment requires, I wasn’t surprised to hear her say that the first thing that came to her mind was the line in the Song where the man, the Christ-like figure, is calling the woman, who is scared, out from the cleft of the rock. He says: “Let me see your face, for your face is beautiful, and let me hear your voice, for your voice is lovely”(Song of Songs 2:14b).

“Imagine Jesus saying that to the wounded who aren’t safe but are behind the cleft of the rock, whom He’s wooing, and calling the woman, and she’s scared. It’s evangelical, he wants her to share the news about who He is,” Byrd stressed.

“So maybe it’s the wounded people whom we can also learn from, whom we need to learn from.”

Brandon Showalter has a bachelor's degree from Bridgewater College in Virginia and a master's degree from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Listen to Showalter's Generation Indoctrination podcast at The Christian Post and edifi app Send news tips to: [email protected] Follow on Facebook: BrandonMarkShowalter Follow on Twitter: @BrandonMShow