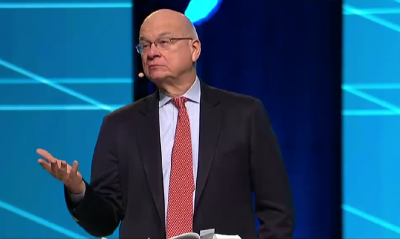

Tim Keller: Right or wrong?

New York church planter and author Tim Keller has been the focus of recent controversy. James Wood in First Things, an admirer, suggests Keller’s brand of “winsome” Christianity appealing to urban elites is past its shelf life. David French responded with a defense of Keller’s so-called “third way” that rejects Christian fidelity to partisan tribes.

Keller is one of America’s most influential Protestant voices. He is ordained in the conservative Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) and founded Redeemer Church in Manhattan in 1989. That church has been very successful and helped create a new, high-brow evangelical subculture in New York City. Keller’s example and writing inspired other urban church plants, many associated with the PCA.

Almost 20 years ago I occasionally attended one of those church plants in DC. It met in a glorious old downtown Methodist church that seated 500-600. The evening service filled every seat, almost entirely of young people in their 20s and early 30s, and contrasted with the struggling United Methodist congregation, which was down to dozens. That Presbyterian church continues to thrive and planted other churches. It is theologically conservative of course, but years ago a friend who visited there told me it was liberal because they discussed recycling, which caused me to smile.

Keller is now age 71, retired, and has cancer, although thankfully doing well, it seems. He leaves a tremendous legacy by demonstrating that thoughtful orthodox Protestantism can be planted in urban areas and appeal to educated young professionals. Much of white middle class Protestantism left America’s cities in the 1950s and 1960s. Keller’s influence introduced a new generation of churches into the cities that were mostly white but more racially diverse than the old Mainline Protestantism. Over years when I have travelled, since traditional Methodism is often scarce in large cities, I have sometimes attended Reformed urban church plants inspired by Keller and am invariably impressed. The congregations are mostly young, the clergy thoughtful, the worship is serious and traditional but with pizzazz. A Methodist bishop once told me he didn’t appreciate Keller because he’s too Reformed. But sadly there’s no Methodist equivalent to Keller, from whom Methodists can learn much.

It could be that Keller’s example of church planting is reaching the end of its widespread application. If so, it is unclear what will replace it. But it has served a godly purpose and created urban space for thoughtful Christians that might not have otherwise existed. In his critique, Wood appreciates Keller’s positive legacy but thinks his style of “third way” Christianity that strove to avoid culture war controversies is no longer viable. Secular culture was more neutral towards Christianity 30 years ago, he notes. But under the current more adversarial conditions, such detachment is no longer sustainable. Bolder stances against this adversity are now needed.

Wood’s critique reminded me somewhat of my attitude towards Billy Graham when I was young. Graham seemed to me like a relic from the 1950s who was too tame, too benign, too nice, too avoiding of controversy and confrontation, somewhat dull, appealing to old people at church but no longer relevant. He represented Reader’s Digest Christianity. I preferred more hardnosed polemical Christianity. In later years I more fully appreciated Graham’s approach, which was conciliatory, without compromising doctrinal essentials. Whatever his faults, Graham advanced the Gospel more than any of his critics. Once Jerry Falwell Sr, amid his Moral Majority battles, flew his private plane to see Graham and reputedly told Graham to keep doing what he was doing, not to step into Falwell’s battles.

Graham of course was chiefly an evangelist and not a public theologian. Keller is more intellectual and is a public theologian. But his perspective as a church planter informs his public theology. What kind of witness will work with young urban professionals? His recipe was fairly successful, but it is not the final word, and he never claimed it was. In his responsive essay, French recalls the 1990s in New York were not necessarily neutral towards evangelical Christianity, which then barely existed in the city, except in the historic black Protestant churches, which was a different brand. Church plants had to litigate for years to get equal access for renting public buildings for worship. Urban elite culture has perhaps NEVER been very friendly to evangelical Christianity. In the 19th century and early 20th century such preachers targeted saloons, brothels, and casinos, which was bad for business, and a threat to corrupt urban political machines.

Mid-20th century Mainline Protestants were tamer and more unthreatening, but their churches emptied as post-WWII middle class white Americans relocated to the suburbs.

Today’s secular hostility to Christianity focuses almost entirely on the church’s traditional teaching about sex and gender. Secular culture is indifferent to doctrines about the Trinity or salvation or the Bible’s miracles, topics of great conflict in the past. Postmodernity mostly declares: Spiritually believe whatever you want! But insisting on particular moral norms about sex and gender is deeply controversial. Keller firmly upheld orthodox teaching about sex but did not highlight that teaching. Likely many of his worshippers have liberal views. In recent years I lunched with the Keller-inspired DC pastor who told me after the Supreme Court affirmed same sex marriage his church, for clarity, posted their orthodox view on marriage. Some parishioners were distressed, but the church moved on.

The Keller approach somewhat recalls the early Methodist approach to slavery. Methodism opposed slavery, but Bishop Francis Asbury soon realized that Methodist-association with anti-slavery would kill Methodism in the south, cutting Methodism off to white and black audiences. Asbury never changed his views on slavery, but he stopped talking about it publicly. Was he wrong, or right? Had he insisted on a strong anti-slavery stance, maybe Methodism would have disappeared from the south. But maybe also there would have been a wider resistance to slavery that could have led to a peaceful abolition instead of the Civil War. This side of the eschaton, we will never know.

We do know that all clergy and every church must operate in a particular culture that entails accommodation. Nobody has the pure virtue, pure courage, and opportunity to exercise complete and faithful loud Gospel proclamation at all times where they are. Pastors in “red state” regions carefully navigate on some issues, just as pastors like Keller do in “blue state” regions. Even the best, wisest and most faithful congregations will only tolerate so much challenge. Every church requires discretion and conciliation. Not everything can be openly and forcefully articulated. No congregation is comprised exclusively of sanctified saints who will hear and heed the full Gospel.

Maybe Falwell Sr.’s advice to Billy Graham to keep doing what he was doing was wise for acknowledging Graham’s particular vocation. Not all Christians, whether shepherds or flock, are called simultaneously to the same fields. God has powerfully used Tim Keller, just as He used Billy Graham, and millions of others who were incomplete as individuals but who collectively comprise God’s Church across time and culture. Whom will He use next? Of course, all of us are chiefly called to ask ourselves: How is He using me?

Originally published at Juicy Ecumenism.

Mark Tooley became president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy (IRD) in 2009. He joined IRD in 1994 to found its United Methodist committee (UMAction). He is also editor of IRD’s foreign policy and national security journal, Providence.