When Southern Baptists officially apologized to all African-Americans

This first-person article was originally published inBaptist Press.

CHARLOTTE — Saturday (June 20) marks the 25th anniversary of a seminal moment in the life of the Southern Baptist Convention. Messengers to the 1995 SBC Annual Meeting voted overwhelmingly to pass the "Resolution on Racial Reconciliation on the 150th Anniversary of the Southern Baptist Convention."

Every Southern Baptist I know who was privileged to be in Atlanta that day will tell you it was one of the most memorable events in their lives. But how did the Racial Reconciliation resolution come to be? What caused it to resonate at such a deep level with Southern Baptists, black and white?

It is a story worth telling. When I was elected in 1988 as the executive director of the Christian Life Commission (since renamed the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission), I was the first undeniable conservative resurgence leader elected to lead a Southern Baptist entity. And the Christian Life Commission (CLC) was not just any entity. It was a gathering place where socially (and often theologically) liberal Southern Baptists encouraged one another in their social activism including civil rights and integration.

After my election, there was much speculation that with the CLC now becoming an uncompromising advocate for pro-life issues, civil rights issues would be de-emphasized. This media speculation was given a rocket boost by negative remarks about Martin Luther King Jr. made by one of the CLC trustees.

What the public did not know was that the trustee's attack on Dr. King was probably provoked by my having praised Dr. King and his tremendous contributions to our country during interviews and discussions leading up to my election as executive director.

In my interviews with the CLC search committee and in a multi-hour interview with the full board of trustees, I expressed my deep appreciation for the CLC's uncompromising stand on racial equality and integration. I shared with the trustees that as a teenager in the 1960s, it had been very important to me that the CLC was on the right side of the race issue when far too many institutions in Southern Baptist and American life were on the wrong side.

I also expressed my great disappointment that America and Southern Baptists had not made more progress on race since the heady victories of the mid- and late-60s civil rights laws drove a stake through the heart of de jure legalized segregation.

Before the trustees voted to elect me, I told them that I believed the race issue was a right versus wrong issue, not right versus left or conservative versus liberal, and that under my leadership the CLC would champion racial reconciliation.

Immediately upon becoming executive director in October 1988, I began planning a CLC conference on racial reconciliation for January 1989 – the first official public event under my administration. One of the first things I did was call Foy Valentine, who had been the CLC's executive director for 27 years (1960-1987) and had taken bold stances on integration and civil rights from the 1950s onward.

I told Dr. Valentine that we were holding a conference on racial reconciliation and I wanted him to be one of the plenary speakers. I said, "Dr. Valentine, my friends will be very upset with me for inviting you, and your friends will be very angry if you accept, but the issue of racial reconciliation is bigger than our friends." I believed it was very important that there be a seamless passing of the baton on the race issue from his administration to mine, and that it would be symbolized by his being a conference speaker.

He accepted the invitation and later informed me that his liberal friends were indeed livid that he had agreed to be a speaker. I assured him a verbal blow torch had been turned on me by some of my conservative friends for inviting him to speak, but the issue was indeed much more important than our friends, liberal or conservative. He agreed. The conference was well attended and succeeded in cementing racial reconciliation as a high priority for the CLC.

I also convened what the CLC called a "consultation," an off-the-record, two-day meeting at the SBC building in Nashville with six black and six white Southern Baptist leaders to foster a frank and honest conversation about racial reconciliation in the SBC. We started with dinner in the evening, followed by an approximately three-hour discussion.

The next morning after breakfast, one of the black pastors opened up the discussion time with this pronouncement: "Dr. Land, you white people are very complicated people. You don't always mean what you say, and you don't always say what you mean. So, we caucused last night, and we've concluded that you mean what you say and so we are going to tell you the truth."

He then said: "You don't realize how badly you have hurt us. We don't mean you personally, but white Christians. It is one thing to be discriminated against by white people. It is something entirely different when you are discriminated against by Christian brothers and sisters."

I believe the real "birth" moment of what became the 1995 Racial Reconciliation Resolution was that consultation in Nashville. I believe the Holy Spirit used that opening statement – "You don't realize how badly you have hurt us" – as the spiritual catalyst to help me understand, and to help others understand as well, that while the SBC had denounced racism from at least the 1960s onward, it had always been in the more impersonal third person, rather than the much more personal first person.

As months went by, it became clearer and clearer to me and to others I spoke with, black and white, that Southern Baptists needed to acknowledge our institutional complicity in having supported or at least acquiesced to racism and segregation. And that we needed to apologize to our African American brothers and sisters for the terrible hurt that support for grievous racism had caused.

I began to talk with an ever-growing group of Southern Baptists, black and white, about the need to pass such a "first-person" resolution, and when and where would be the best place to do it.

In the process we had to deal with those who objected to Southern Baptists' "repenting" for the sin of our ancestors. People would say to me, "We are not Mormons; we can't repent for our ancestors," and that is certainly true.

I cannot repent before God for my direct ancestors who were slave holders any more than I can earn points with God for my direct ancestors who were abolitionists. However, we can, should and must express sorrow for the sins of our forbearers and apologize and seek forgiveness from those who suffered the enduring consequences of their sins.

Many of us felt the time had come as we approached the 1995 SBC Annual Meeting in Atlanta, where we would celebrate the 150th anniversary of our founding. I went to then-SBC President Jim Henry and shared with him that before we celebrated the anniversary, we had some really dirty linen in the closet that we needed to address. He enthusiastically affirmed this and agreed to suspend the Convention's rules and have the resolution reported a day early so we could pass the Racial Reconciliation resolution before we celebrated our 150th birthday.

When you read the resolution, you will see the spirit of repentance, grief and yearning for spiritual reconciliation that energized it. It was graciously received by so many of our African American brothers and sisters. The resolution made a real difference, thank God.

However, I am grieved that we have not made more progress in transforming our Southern Baptist Convention and our nation in dealing with America's "original sin" of racism.

When dealing with racial issues, I always go to the Bible first and then to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In the Bible, I see racism condemned from beginning to end. Genesis tells us "God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him" (Genesis 1:27) and "Adam called his wife's name Eve: because she was the mother of all living" (Genesis 3:20, emphasis added). Consequently, there is only one race – the human race. Scientific research is now confirming what the Bible told us all along – we all come from one common ancestor.

In the New Testament, we are informed that "God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him" (Acts 1:34), and "He made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth" (Acts 17:26).

And finally, of course, we have the all-encompassing language of the best-known verse in the entire Bible, "For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life" (John 3:16, emphasis added).

When I turn to Dr. King, I find him never wavering from a deep commitment to racial reconciliation. As Dr. King's niece Alveda recently reiterated, "Martin Luther King preached love, not hate; peace, not violence; universal brotherhood, not racism."

Dr. King, in his incandescent 1963 "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" (which I believe ought to be required reading before any American high school senior may graduate, right up there with the "Gettysburg Address"), Dr. King reminded Christians that our divine command is to be spiritual thermostats, setting the spiritual temperature of society, not merely thermometers recording its temperature.

Am I disappointed that we have not been more successful in quelling the demons of racism in the last quarter-century? Yes! However, one of the consolations of advancing years is the gift of context provided by time and experience.

Born in the first year (1946) of the "Baby Boom," I am a child of the civil rights era. I saw the death of Jim Crow and segregated drinking fountains and restrooms. I witnessed the enfranchisement of millions of African Americans in the 1964 and 1965 Civil Rights Acts and the 1967 Voting Rights Act. I have witnessed and experienced the highs and lows since then. Consequently, I not only see the gap that remains, but the distance traveled and the progress that has been achieved.

May we all draw inspiration to complete the journey to the fulfillment of Dr. King's dream of a country where all people are "judged not by the color of their skin, but the content of their character."

If length of years has taught me anything, it has taught me this – the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ is the only way to complete the journey to the fulfillment of Dr. King's dream for our country.

The salt of the law can change actions, but only the light of the Gospel can change attitudes. The salt of the law can change behaviors, but only the light of the Gospel can change beliefs. The salt of the law can change habits, but only the light of the Gospel can change hearts.

Let us not weary in well doing. May God give us the strength and the wisdom to finish the journey together, arm in arm, redeemed and reconciled heart to heart. Let us be about our Father's business.

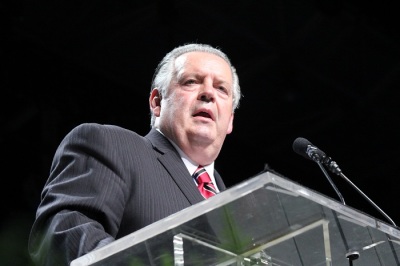

Dr. Richard Land, BA (magna cum laude), Princeton; D.Phil. Oxford; and Th.M., New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, was president of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (1988-2013) and has served since 2013 as president of Southern Evangelical Seminary in Charlotte, NC. Dr. Land has been teaching, writing, and speaking on moral and ethical issues for the last half century in addition to pastoring several churches.