Why I'm no longer a cessationist

My relationship with Jesus was revolutionized in my late 20s when two things happened: 1.) I abandoned my long-held belief in cessationism and 2.) my marriage began to fail.

The desperation and agony of the latter drove me straight to the foot of the cross and deepened my relationship with and dependence on Christ like nothing else ever has. I saturated myself in His Word. I spent hours on my face in prayer.

My dedicated parents had raised me in a Reformed Presbyterian Church and school. They sacrificed a great deal to afford me this opportunity, and it’s not one I take for granted. This is where I learned to think critically, prioritize objective truth above my feelings, pore over the Scriptures, and prepare to have an answer for my faith, which I took very seriously, mostly out of fear of being struck down with a lightning bolt if I colored outside the lines, but that had as much to do with my trauma lens as it did with the actual teaching of the church.

I could write paragraphs about the merits of Reformed Christian living. By and large, these are people of discipline and depth. They are sincere in their desire to obey Christ, and they possess a boldness that puts many other denominations to shame. They are willing to take a strong stand for the things they believe in. This always resonated with me as a passionate person with similarly fierce conviction.

But there are flaws, too, and I’ve come to believe that cessationism is one of the biggest ones. Cessationism, as one of my favorite pastors used to say, is the belief that the miraculous petered out when Peter petered out. It says that miracles don't really happen anymore, that spiritual gifts like prophecy and speaking in tongues are largely hysteria rooted in desperation and deceit. Cessationism is a lie that seeks to squish God into a box that people can predict and ultimately control.

And I clung to Reformed theology precisely because of that control and false assurance it provided me. There was a script for everything. Every life question could be answered via the Heidelberg catechism or the Westminster Confession of Faith. Reformed people often feel close to God by knowing about God, and I acquired this knowledge like a sponge, ready to answer every theological quandary that presented from the doctrine of total depravity to the merits of premillennialism. My ability to answer any question or doubt that arose created a false sense of safety for me; as long as I had the answer, I would be okay. My theology was marked by order and tidiness — everything in its place, no room for mess or uncertainty or doubt. We had everything nailed down to a science. I even knew which verses of which hymns were acceptable times to raise my hands toward Heaven. Anyone who operated outside these parameters was to be held in deep suspicion.

And I was willing to ignore a lot of ideas that were harmful to me in exchange for this assurance. I convinced myself it was a form of biblical obedience, of dying to self. Their views on women, for example, I was willing to stomach them. A superficial reading of some decontextualized verses led me to believe that God really did want women silent and submissive, so I did my best to make peace with it, resolving my cognitive dissonance by repeating mantras like, “God’s ways are higher than mine. It’s okay if I don’t understand it. He’s still good.”

And this mantra, is, of course, the truth, which is why this territory was so confusing for me. It’s objectively true that God is God and that He gets to do what He wants and I don’t always have to understand it. But one of the things that was profoundly lacking in my experience of God was an actual relationship with Jesus Christ, the lover of my soul and the lifter of my head. I was substituting my knowledge about God for an actual relationship with God.

It wasn’t working out so well for me.

My paint-by-numbers Christianity had nothing to offer me when my life was falling apart. It had no answers or weapons for the intensely spiritual war raging around me and wreaking havoc on my life. I’ll never forget going to my pastor in the depths of my despair and needing guidance. He handed me a book by Francis Schaeffer and quoted, “You’ve just got to ride your tiger.”

And that was it. Pull yourself up by your bootstrap theology that said, “God is good. Now suck it up.”

I needed so much more.

As a child, I experienced the demonic with startling frequency and intensity. As I grow in my faith and understanding, I realize this is a typical experience for abuse survivors. Even those who don’t believe in God often have personal, visual experience with the demonic realm. We have fancified, clinical language to describe and explain these experiences in a way that feels less mystical and more logical: We often hear about things like “sleep paralysis,” which is often what happens when people are under demonic oppression that renders them completely unable to move or even open their mouths to cry out for help.

For me, this experience was so pervasive and so intense that I slept with the light on well into my 20s. When I was pregnant with my son and fighting some of the most extreme spiritual warfare of my life, I actually needed my mentor to sleep in the bed with me because the terror was so intense. I could see demons in my room at night. I could feel them. I could hear them. One night it was so bad that I ran from my room and crawled in bed with my sister. She bolted upright in the bed and asked, “Kaeley, What did you bring in here with you? It is so dark!”

Reformed Christianity did not have an answer to her question. I was referred to a psychiatrist, and they put me on lithium, which did nothing to help the actual problem. My experience was quickly written off as mental illness rather than demonic oppression. And the shame that came with this diagnosis made me seek to hide, isolate, and retreat further into the oppression rather than expose, rebuke, and conquer it.

While we would loudly read passages from the Bible about spiritual warfare, there seemed to be a disconnect between what we said we believed and what I was learning in church. I was actively taught to distrust the very believers God intended to use to help me, and like a diligent, obedient servant, I did.

But eventually, I came to the end of myself. After years of working to overcome abuse trauma and my ensuing poor decisions, I had married an abusive man who continually cheated on me, and I was just so broken that I literally couldn’t pull myself back up anymore.

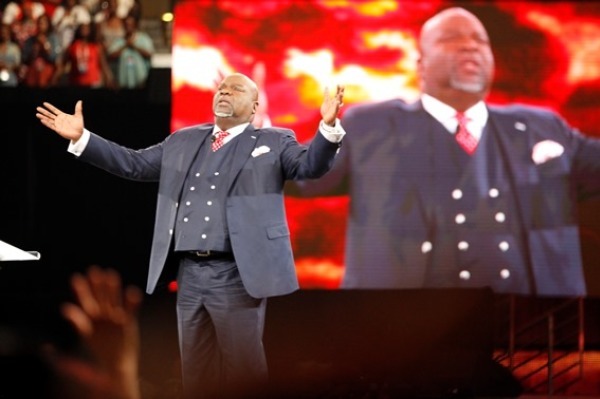

My best friend Elli (one of the most brilliant, anointed people on planet earth), seeing my desperation, sensed that I was finally in a place to be ready to receive. She dragged my limping behind to her charismatic church with her one night, and I just broke. As the worship team sang, I hit my knees, held up the fractured pieces of my theological idols, and said, “Take them, God. I surrender it all. Give me what I need. Fix me.”

That night, the pastor came and placed his hands on me as he prayed, and I felt a powerful surge of almost electrical energy surge through my body. It knocked me to the ground. I don’t even care how crazy this makes me sound. I was the most skeptical person in the entire world. Things like this did not happen to me. But there I was on my backside, face to face with the undeniable power of a living God who cared enough about me as an individual to show up and remind me of His tangible presence. You can’t unknow this once you experience it. And I’ve experienced it over and over again since then, through prophetic words, through visions, through miraculous provision, through divine appointments.

In many ways, this was the beginning of my deconstruction journey. If everything I believed up until this point about how God operated was wrong, what else was I missing? I’ll be honest — abandoning cessationism, for me, was like an Amish person coming out of the Amish lifestyle; I had to hold lightly everything I thought I knew about God and somewhat blindly figure out where the new boundaries were. And it wasn't a pretty process.

As part of this, I prayed for a word about what to do with my failing marriage, and what I kept hearing God say was "Beauty for ashes." In fact, the verse came to me in so many different ways and forms over a short period of time that when prompted to change the password on my computer, I changed it to "beauty for ashes." I interpreted this to mean that God was going to restore my marriage and heal my husband.

I believed this fervently and with a childlike faith. Any time I would be tempted to call it quits, inevitably some couple at church that I had never met would approach me and say something like, "We feel like we're supposed to tell you that God wants to heal your husband." They had no business knowing that my husband even needed healing. So I would stay and I would pray.

My poor family would plead with me to see reason, but faith, as I understood it, was profoundly unreasonable. That's what made it faith. My husband broke a door over my head. Still, I stayed. "It always gets worse right before breakthrough," I remember telling my family. He got a girlfriend. Still, I stayed. "God's arm is not too short. I know what He told me," I insisted. He trapped me in parking lots and screamed obscenities at me in front of my children. "But God wants to heal Him," I told my despairing family members.

I remember sitting for hours as I pleaded with God and doodled drawings. You can see my tenacity in the pictures I drew. I resolved to "set my face like flint" and to touch the hem of His garment. Time and time again, I prayed, "I won't let you go until you bless me."

I clung to the promises I was convicted I had received for seven years. (Seven, you will note, is the biblical number of completion.) We divorced shortly after he got his sixth or seventh mistress, and it crushed me.

I had been so faithful. I had been so obedient to what I thought God was telling me. I had believed beyond the point of reason in God's power to change my circumstances. I had made myself a fool in my defense of what I thoroughly believed was true: God was going to give me beauty for ashes in my marriage. He wanted to heal my husband.

Had I heard wrong? How could I be so close to God and so completely delusional at the same time? Were those words not from His voice? Where had I gone wrong? And why am I sharing all of this embarrassing baggage on a public forum that will likely subject me to further ridicule?

These are the types of missteps that keep Reformed people from stepping out into these waters in the first place. These are the types of embarrassments they want to mitigate for the greater good. This was why they embraced cessationism. But here’s what I’ve learned:

God always rewards obedience and faith — even when we get it wrong. He judges our hearts, and faith (even when misguided) is not wasted. It will yield fruit; even if the fruit is not exactly what we expected.

Did I mishear God in regard to my marriage? Not really. He did want to bring me beauty for ashes. And He has been faithful to do just that. He brought me a new husband who loves Jesus and my kids, who hates porn, who would never lift a finger to hurt me, and who actually loves me and cares about my heart. My life is so much richer now than it ever could have been with my ex. And I think God wants to heal my ex, too.

Where I went wrong was in believing I knew what God's solution was going to look like. I took the words He gave me and painted my own preferred narrative. And I was really, really wrong.When we make bold proclamations about what God will do, proclamations that include specifics like timelines that don't come to pass, we do tremendous harm to the credibility of charismatic teachings, and there needs to be accountability for it. I tread lightly here, but it needs to be said, that I’ve seen people do similar damage in their prophetic words about presidential candidates, and accountability should be made here, too.

When my unbelieving siblings saw me holding out faith in something that was ultimately a delusion, I damaged their ability to trust even the legitimate parts of my faith. I grieve this. I screwed this up. I need to name this as a failure on my part. It's not okay for me to just whitewash the whole affair and say, "God changed His prophecy to me, and you need to keep coming along with me on this ride." How could I possibly expect them to?If your faith is neat and tidy and perfectly ordered, if it doesn’t allow for mistakes or a bit of a mess or a much-needed wrestling match with God (Genesis 32:22), you aren’t going to walk away with a limp, but you won’t walk away with a new name either. God wants us to take some risks and step out of the boat and believe that He will help us walk on water. Faith cannot be passive. It needs to be active. It needs to be bold. It needs to be audacious. Real faith does not look at mountains and say, “Lord, if it’s your will, I surrender to this obstacle in my life.” Real faith looks at the obstacle and commands it to move.

Scripture commands us not to hold prophecies in contempt, and I don't and won't. But I will also be faithful to the remainder of that verse, which tells us to test every spirit, and if some of these spirits aren't passing that test, we need to be able to say so. This requires a willingness to hold truth in tension, to wade into grey areas, to be okay with uncertainties, to openly name our doubt and bring it to the foot of the cross, and wait upon the Lord for answers. For me, remaining tethered to Reformed theology was something of a choice to cling to the shoreline while a powerful God was calling me to step out upon the water.

All I know to say is that the well of God’s power is a chronically untapped source. Many of us cling to the shoreline of a stagnant, ordered faith because we’re afraid of drowning in the waters of our doubts. What if “riding our tiger” looks like yielding our sense of control to the Lion of Judah?

I’m reminded of a quote from Narnia, where Susan asks Mr. Beaver if Aslan is safe: “Safe?” said Mr. Beaver, “Who said anything about safe? Of course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the king, I tell you.”

Kaeley Harms, co-founder of Hands Across the Aisle Women’s Coalition, is a Christian feminist who rarely fits into boxes. She is a truth teller, envelope pusher, Jesus follower, abuse survivor, writer, wife, mom, and lover of words aptly spoken.