American evangelicals give $58K to save persecuted Muslim family; US still denies asylum

Afghan interpreter Muhammad Kamran said he felt like he was part of a brotherhood when he aided the United States military in its fight against terrorism in Afghanistan from 2004 to 2014.

Kamran, a Muslim father of four and a teacher, served as a mission interpreter who helped recruit and train other Afghan nationals to interpret and translate for U.S. troops as they fought to eradicate al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

As a 19-year-old at the time he began, Kamran felt called to assist the Americans as they fought the radical extremists he considered to be the “enemy of humanity.”

“They were calling me brother,” Kamran said of U.S. soldiers during his 10 years of service aiding various branches of the U.S. military and the United Nations. “They were another nationality and another culture. I was from another country and of another religion but there was no difference for us. We were living with each other. We were eating with each other. We were sleeping in one room. There was no problem for us.”

But four years later, Kamran is among thousands of Afghan translators struggling to receive help from the U.S. government and the international community as they face death threats and violence for aiding the fight against terror.

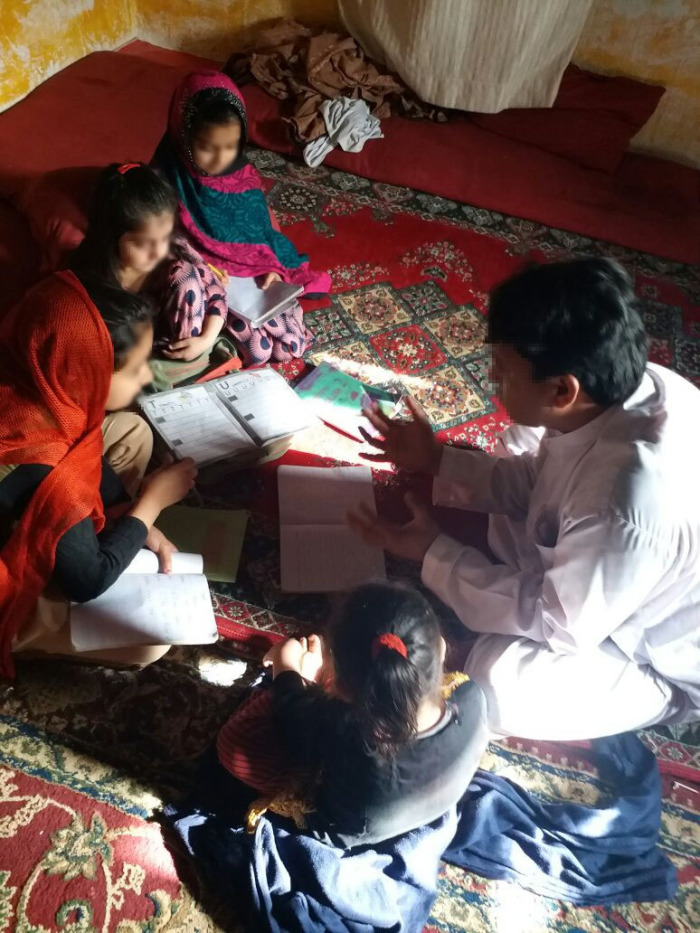

As for Kamran, his wife and four girls, they have been forced into hiding and are living as illegal immigrant refugees trapped in neighboring Pakistan because of his decision to aid the U.S. — a “sacrifice” that he says he is proud of despite the fact that it has cost him his home, his cars, his wealth, and nearly his life.

Because he aided the U.S. mission, the Taliban is looking to kill Kamran. The Sunni radical terror organization that calls itself the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” spread lies throughout Kamran’s community in the Nangarhar Province that he's a Christian looking to convert Muslims to Christianity — a charge that put a large target on his back inside his home village.

Today, the Kamrans live under the constant threat of Pakistani military and police raids. If Kamran is caught, advocates fear, he risks being killed by the Pakistani military or turned over to the Taliban.

Despite this, Kamran and his family were denied asylum by the very government he risked his life to assist.

Even though a generous American evangelical Christian family has spent over $58,000 to help keep the Kamran family alive over the last couple of years and offered to shelter the family at their California farm, a request for the Kamrans to receive even a one-year humanitarian stay was denied last November by the Department of Homeland Security.

The denial comes as tens of thousands of Afghan and Iraqi citizens are on a waitlist for Special Immigrant Visas designed to allow translators and interpreters who worked with the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan to seek refuge in the U.S.

Yet, preliminary State Department data indicates that there was a slowing in Special Immigrant Visas issued for Iraqi and Afghan interpreters in 2018.

The number of Afghan SIVs issued in fiscal year 2018 is nearly 9,000 fewer than in 2017, and about 500 more than the number of Afghan SIVs issued in fiscal year 2015 under the Obama administration, and about 1,800 fewer than the Afghan SIVs issued by the Obama administration in 2014.

Kamran's case was first denied under the Obama administration in 2016 and the ensuing appeal and application for humanitarian parole have been denied by the Trump administration.

The Kamran family was denied humanitarian parole by the U.S. government without a thorough review of the case or an explanation as to what the government’s security concern with his family is, according to the family’s advocate, Kristy Perano, who along with her parents and brother have financially sacrificed to help keep the Kamran family alive.

“I have worked 10 years for the security of the people," Kamran said. "I did not care about the religion. I work for every religion. I work for every human and every country. But now, they say we are a security problem and I don’t know why. How did I become security problem? I don’t know this still.”

Fighting the war against terror

Shortly after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. got involved in the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan in which the U.S. sought to push the Taliban from power.

Being “strictly against terror,” Kamran began helping the U.S. Army in 2004. He worked out of the Kabul Military Training Center, where he helped interpret for Army troops in charge of training recruits for the Afghan National Army.

“My English was very good and the American people liked me a lot,” Kamran recalled. “They decided that they should push me to the missions and I should become a mission interpreter. So they gave me a good post and also make me mission interpreter.”

In 2006, Kamran began working with the U.S. Navy at Camp Lightening in Gardez Province where he worked on many training and humanitarian missions.

One of those was an assignment to assist the Navy in its efforts to institute a training program to teach the Afghan recruits to drive trucks. It was during this time that Kamran worked a lot with former Navy Lieutenant Karsten Daponte, who spent six months stationed in Gardez.

“He and I spent hours and hours in the truck and having some laughs,” Daponte, who retired from the military and now works in the energy sector, told CP. “Being in the front of the truck with Muhammad there with me, it was a shared experience and I will never forget that in my life.”

Also in 2006, Kamran was transferred to the Jalalabad Air Base in his home province of Nangarhar. There he worked with different branches of the U.S. military and went on night missions with U.S. Army 10th Mountains teams to arrest Taliban insurgents.

“I come to my province and I knew all the places that were [bad] and which were [good],” he explained. “I was providing information to the U.S. troops and U.S. Army. They were doing the operation and I was participating in that. The people know me very well. Taliban got a lot of information about me.”

Kamran said that over time he was “becoming a little famous” within the Taliban.

The 'enemy of Islam'

The terrorists, he said, would frequently call his phone and threaten him. He was even forced to change his number and block callers.

“They were trying hard and hard to find me and get me,” Kamran explained. “They were asking people [in my community] to help them.”

“[Muslim clerics] told them that they should announce me as a Christian — not only a Christian but a dangerous Christian who is converting the people from Islam to Christianity,” Kamran said. “These people accepted it.”

Kamran said that the Taliban eventually began threatening people by telling them that if they have any relationship with him, they will be killed.

“They announced all our family as Christians and that our family should be killed. They would say, ‘They are Christian and their son is also Christian, and he is converting people to Christianity. He is the enemy of Islam and enemy of Muslims,’” Kamran recounted. “They directly announced me as the enemy of Islam. They sent letters to the mosque and said that I killed a lot of Taliban. I did not do that but they were blaming me a lot and they were making a lot of problems for me.”

Kamran said that the “most dangerous” time for his family began in 2014 after most U.S. troops had been withdrawn from Afghanistan. He said that people in his village and even people who he helped tutor were no longer friendly with him anymore.

“The Americans had gone and the job had gone and everything was finished,” Kamran explained.

Although there were around 100,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan at one point, that number now stands at over 14,000 even after President Donald Trump's troop increase.

“They (U.S.) did not care about me because they left Afghanistan. Then, my house got burned. [The Taliban shot] my brother. My two friends were killed. One man who I trained, they killed him also. The other friends who took a job as an interpreter, they arrested him, break his hand and feet and take all his money, his home and his car. Now he is a U.N. refugee in Canada, I think. I don’t have any contact with him. Finally, my dad and my mom told me that you don’t have to stay here anymore.”

Kamran turned to the government for help. He went to the district governor who offered him little help other than telling him to seek help from the United States.

Fleeing Afghanistan

With their lives in danger in Afghanistan, Kamran and his family fled Afghanistan on a five-day journey to Pakistan in 2014. According to Kamran, his family went without food for two days and only had dirty water to drink.

“I was walking in the mud for five days without boots and without shoes,” he said. “At that time, one of my daughters was only 6 months [old]. In different places, I got arrested but I was giving a bribe and I was giving the [officers] money.”

Although Kamran said that he feels fortunate to have fled Afghanistan, the situation in Pakistan is rough.

“My home has been raided by the police and by the military. Whatever I had here, the police took that from me,” he detailed. “I could not even buy one tablet when my kid got sick. I did not have the money to pay the rent of my house.”

Kamran has to regularly flee his house because of frequent immigration and anti-terrorism raids. Through connections, Kamran is tipped off when there is going to be a raid in his area. In some instances, Kamran has been caught by authorities but has paid officers with bribes so he won’t be processed and they won’t learn his identity.

At one point, Kamran and his family were kicked out of their home by a landlord because they couldn’t pay the rent. The Kamrans can’t leave their house out of fear of being arrested. This means that Kamran isn't able to work and make a living.

The Kamrans initiated a refugee case with the U.N. in July 2014 and the case was referred to the U.S. in March 2015. In February 2016, the Kamran family was denied asylum by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services for “discretionary” reasons.

Later that month, the Kamrans filed a request for the agency to review the denial of his case, which was eventually denied without review.

“It was in a very critical situation I was in,” Kamran said. “There were a lot of problems I was facing. Then I met Kristy.”

The Perano family

Perano, a 29-year-old Cornell University Ph.D candidate from California, has dedicated her time and money to aid the Kamran family over the last couple of years.

Perano has teamed up with her parents (Ken and Susan Perano) and her brother and sister-in-law (Tim and Julianne Perano) to provide money to the Kamran family to pay rent, legal fees, food, and living costs.

Because the Kamrans can’t work, the Peranos pay for nearly everything.

For food, the Peranos pay a friend of Kamran who buys groceries and delivers them to the family.

The Peranos have also paid for a doctor to come provide emergency surgery when Kamran was stabbed by thieves and seriously wounded when he fled the house during a military and police raid. As an illegal immigrant, Kamran could not go to a hospital.

Split nearly three-ways between the family, the Peranos have aided the Kamrans with over 18 months' worth of living expenses and medical bills.

Should the Kamrans ever be allowed to come to the U.S., the family would live on the Perano family's farm in Jackson, California.

Now residing in Ithaca, New York, for school, Kristy Perano has dedicated her time to advocating on the Kamran family’s behalf as she completes her degree in biological and environmental engineering.

She initially heard about the Kamran family’s ordeal through her volunteer work with the organization No One Left Behind, an advocacy nonprofit founded by a military vet whose life was saved by an Afghan interpreter who was denied asylum.

Perano was able to get connected with Kamran after learning more about his situation. She tracked down an immigration attorney who specializes in refugee cases to take on Kamran’s case at a reasonable cost.

“For me, I see it as a fight for justice. There is a repeated theme in the Bible about fighting for justice for oppressed people,” Perano, who attends Bethel Grove Bible Church in Ithaca, said. “I am spending 30 percent of my income on this now and 10 percent is kind of a traditional guideline but not a cap.”

“If we stop, they are going to die and we know that,” Perano added. “We have gotten to know them well. Muhammad isn’t a Christian but has a high opinion of Christians. I don’t have the expectation that he is going to convert to Christianity, but I also have a belief that he deserves to live in a free society that Jesus would want [us] to protect and not leave [the Kamran family] to be murdered by the Taliban.”

Perano has created a GoFundMe online fundraising page to assist the Kamran family.

Filed for humanitarian parole

With the help of Seattle-based attorney Danielle Rosché, the Kamran family filed for humanitarian parole in August 2017.

Humanitarian parole is a “discretionary authority” that “allows for the temporary entry of individuals into the U.S. for urgent humanitarian reasons or for significant public benefit.”

The program enables citizens to submit an application “on behalf of someone who is outside of the U.S. and has an urgent need to enter the country.”

“We are asking USCIS to let them just come here on this temporary basis and we can kind of re-evaluate the asylum claim at our leisure,” Perano explained. “We tried that and USCIS just denied the case. First, they lost it for a few weeks and then they denied it after two days of consideration.”

The case was denied last November over discretionary security concerns that have not been disclosed by the agency.

Perano said that she was somewhat optimistic when they retained Rosché because the attorney had past success in getting humanitarian parole for interpreters and family members who were previously denied asylum.

After the denial, they pressed USCIS Humanitarian Affairs Branch Chief John Bird to see if Muhammad's young daughters could be allowed to enter the U.S. to live with an aunt and uncle who have received asylum. However, Bird claimed last November that the children were also a security concern.

“The case was closed,” Perano said. “That just depressed a lot of people in Congress. As far as I know, that is the only time that USCIS put in writing that they were denying a one-year visa to a 2-year-old child on the basis that she was a security concern.”

“The agency said that since their cases were denied before, they were denying it again because they have security concerns,” she added. “Our lawyer pushed back and said, ‘What are your security concerns?’ They said, ‘We will actually have to go review the refugee case to answer that question.’ They admitted that they hadn’t bothered [to review the case]. They denied the humanitarian case because he had been denied before without even reviewing the original denial themselves.”

Because the denial was discretionary, the agency isn’t legally required to reveal its reasons for thinking that Kamran and his family are a security concern.

Perano lobbied members of Congress to sign a bipartisan letter sent in July to Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen demanding to know more about why Kamran’s asylum and humanitarian parole cases have been denied and to voice concern with the fact that the case was denied on a discretionary basis.

The 38 Congress members are also seeking information on how many interpreter cases have been denied for discretionary reasons and how many refugee cases overall are denied for discretionary reasons.

Despite giving the agency a mid-August deadline, DHS has yet to respond to the congressional inquiry, Perano said.

The Christian Post reached out to USCIS for comment on the congressional inquiry and was told that the agency does not offer public comment on Congressional correspondence and “will respond as appropriate.”

A source with knowledge of the issue told CP that USCIS explained last month that it was still waiting on additional information from the State Department before responding to the letter.

Perano explained that if the agency doesn’t respond by January when the new Congress starts, then Congress will take further action “to get answers from USCIS.”

Perano launched a Change.org petition calling on USCIS Humanitarian Affairs Director John Bird to re-open and approve the Kamran family’s case. Over 50,000 people have signed the online petition.

As she has had success getting humanitarian parole for interpreters under the Obama administration, Rosché couldn’t say whether denials for humanitarian parole for interpreters who worked with the U.S. government or military were more common under the Trump administration.

“[These discretionary denials] seem nonsensical and random to me,” Rosché told CP. “I have worked on cases like Mr. Kamran’s. I have worked cases of elderly Christian women from Mosul who have fled ISIS who were denied refugee status as a matter of discretion.”

Daponte is also perplexed by the situation that the U.S. government has put the Kamran family in.

“They really were putting a lot on the line in good faith to help us help them,” he said of Afghan interpreters. “If we treat people in this circumstance this way and basically cut them loose in a sense, that is a really bad signal to send to our partners whether current or future. Partners and allies might second guess working with us.”

Slowing of visas

The Afghan Special Immigrant Visa program was created through the Afghan Allies Protection Act of 2009 to provide visas to Afghans who worked at least one year as a translator or interpreter for or on behalf of the U.S. government in Afghanistan in order to allow them to resettle in the U.S.

A similar program was created in 2008 for Iraqis working on behalf of the U.S. forces in Iraq.

Preliminary State Department data indicates that the number of Afghan SIV visas issued were cut in half during fiscal year 2018 even though as many as 17,000 Afghans are on an SIV waiting list.

In fiscal year 2018 (Oct. 1, 2017 - Sept. 30, 2018), only 7,234 Afghan SIVs were issued with 1,649 being principal applicants and 5,585 being dependents. By comparison, 16,170 Afghan SIVs were issued in fiscal year 2017 (4,120 being principal applicants) and 12,086 Afghan SIVs were issued in fiscal year 2016.

“In future conflicts, if the United States cannot show that we have protected our interpreters and local aides in the past, when we go into future conflicts, we are going to receive less aid from locals,” Rosché told CP. “From a national security perspective, that is very dangerous for our soldiers going into our future. It’s a moral aspect of helping [them] because [they] helped us but there is also the point that for future conflicts we need our local people to be able to rely on our word.”

Advocates have raised concern about how the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019 passed without the inclusion of additional Afghan SIVs because of budget constraints.

In June, the Trump administration voiced its “disappointment” with the fact that the bill does not include a provision allowing for 4,000 additional Afghan SIVs in the fiscal year 2019.

“Without allocating additional visas, there will be no authority to fully address the current pipeline of eligible individuals estimated at approximately 16,700 or any further eligible individuals who apply before the December 2020 deadline,” a June 26 statement from the White House Office of Budget and Management reads.

Activists and lawmakers have called for a measure authorizing an additional 4,000 Afghan SIVs to be included in the fiscal year 2019 State, Foreign Operations and Relations Programs appropriations bill that funds the State Department.

Sens. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., sent a letter in August to the leaders in the Senate Appropriations Committee asking for the measure to be included in the legislation. Additionally, a group of veteran organizations sent a letter to Congress in September also calling for the allocation of 4,000 Afghan SIVs for 2019.

Advocates are unsure what will happen in the final weeks of the bill’s negotiations. The group Veterans for American Ideals is continuing to lobby Senate Appropriations Committee Chair Richard Shelby, D-Ala., and others on the committee.

“Since both the House and Senate subcommittee reports deemed the SIV program critical, we're optimistic that it's going to happen,” Christopher Plummer, senior media relations associate with nonprofit organization Human Rights First, told CP. “This is a lifeline for our Afghan allies — many whose lives are at risk for their service to us — so the committee needs to step up.”

In August, military leaders reportedly spoke out about the drop in admission of Iraqi interpreters admitted under the Direct Access Program, which replaced the SIV program, during a closed-door meeting at the White House on Iraq, according to Reuters.

According to the State Department data, only 152 Iraqi SIVs were granted to principal applicants and 372 were granted to their dependents in the fiscal year 2018 for a total of 524. In fiscal year 2017, a total of 2,134 Iraq SIVs were issued.

Other nations turning asylum seekers away

In the midst of a global refugee crisis, Western European countries have seemingly taken a harder stance against Afghan asylum seekers in recent years.

According to The Washington Post, Western European nations have rejected hundreds of thousands of Afghan asylum applications in the last two years and deported thousands of Afghan immigrants back to Afghanistan even though the Taliban still controls much territory.

Having been denied asylum by the U.S., Kamran said that he has asked the U.N. to refer his case to another Western nation.

“They told me that it was my fault because I emphasized them to give my case to the U.S. They said that ‘You worked for U.S and even your brothers are not accepting you,’” he recalled. “They said that if they give my case to Canada or Australia or another country, they will ask this question: ‘This person worked for the Americans for about 10 years and they are not accepting him. Why should we accept this person?’”

Abandoned

What makes the situation even more perplexing to Kamran is the fact that other members of his family have been granted asylum in the U.S. in the past several years.

“I don’t know how my brother and my sister and my nephew were cleared and I was not cleared,” he explained. “I was one of the most important persons for the Americans. As I told you before, they were not calling me by my name. They were calling me brother. They were telling me that I was their brother but now I am a security issue.”

Kamran said that it was he who trained his brother, brother-in-law and many other Afghan nationals when they were assisting the U.S. government.

“The government, the friends and family — everybody has left me alone,” Kamran explained. “If I go back to Afghanistan, they will take revenge from me and I will not be alive.”