Discrimination cost black farmers at least $250B in property, law scholar says

Habitat for Humanity joins to tackle 'huge gap' in homeownership

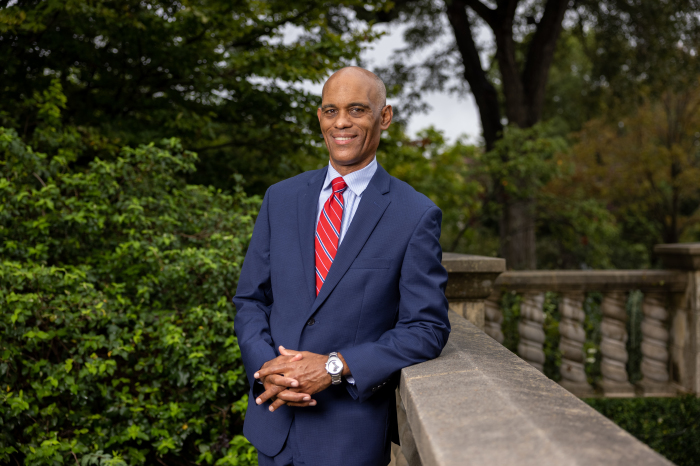

Property law scholar Thomas W. Mitchell, who was a 2020 recipient of a MacArthur "genius" fellowship for his work looking at how black and other disadvantaged Americans have been deprived of their real estate wealth, says black farmers alone have lost millions of acres of land and at least $250 billion in wealth over the last century due to “historic discrimination.”

Mitchell shared the data during a virtual session hosted by Habitat for Humanity Friday to mark the 35th anniversary of the federal observance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, reflecting on King’s vision of “the Beloved Community” — a community that includes diversity and allows for tension undergirded by love and leads to transformation.

“One of the things that we need to acknowledge is the scope of historic discrimination and its fallout. So for example, when we’re dealing with black farmers and the land that they have lost in the last 100 years, which you know, we’re talking it’s at a scale of 15, 16, millions of acres of land, I’m part of a research team that’s looking at the economic consequences of that loss and our conservative estimate of just the value of that property itself is $250 billion,” said the Texas A & M University School of Law professor.

“Our research team … is now trying to build a more robust estimate taking into account things like, when you own property, you can use that property as collateral to finance your children’s higher education and those outcomes you can expect intergenerationally from that,” he said, noting that the losses for black farmers are likely to increase to “several hundred billion dollars.”

A key area of Mitchell’s research focuses on heirs’ property, which is a subset of tenancy-in-common property, which tends to be created in the absence of a will or estate plan and results in “undivided ownership.” This means each of the legally defined heirs own a fractional interest in the property, rather than a specific piece or portion of the property. After several generations, ownership of land and other property, including single-family homes, may be fragmented among many heirs, any one of whom can sell their fractional ownership or seek to force a sale of the land, with or without the agreement of all owners.

His work showed how property laws have worked against black families in both the rural and urban contexts.

“Law and policy has a huge role. In addition to the kind of extralegal means that were used in terms of violence and lynching and physical intimidation, there’s a whole set of laws that have contributed to either preventing African Americans and other disadvantaged families of color from becoming property owners in the first instance but then for those kind of rarified few who have achieved that status, that has then led to them losing property or property rights that they had developed,” he said.

He argued that while the coronavirus has exposed a number of racial inequalities in areas such as health and housing, another area of disparity that continues to dispossess black families of wealth is “estate planning.”

“One of the racial wealth gaps, which is probably not very well known, is a massive racial will-making or estate planning gap in this country,” he said.

He explained that while approximately 62% of white Americans make a will but about only 22% of African Americans do. And while the most educated across racial lines tended to do a better job of estate planning, the most educated African Americans still make wills at a lower rate than the least educated white Americans.

He also argued that while the high watermark for black homeownership in the U.S. was nearly 50% in 2004, that rate is now lower than the 41% that existed in 1968 when the federal Fair Housing Act became law.

“Before the pandemic, we had lost so much ground, we were below the homeownership rate at the time the federal Fair Housing Act had been enacted into law. It’s kind of shocking kind of realization,” Mitchell said.

If legislators and other housing stakeholders are going to fix this enduring problem, he said, the “remedy, it’s got to be to the level of the problem, not things like a token or symbolism.

“You need people in policymaking positions that reflect the diversity of the country so that you have African Americans and Latinos and others who are in important policy positions to develop and direct and to help the policy team overall raise their awareness of problems they might not be familiar with,” he said.

Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity International, said during the virtual session that “we have to acknowledge that housing was absolutely a part of the problem.”

“In the last century, housing policy [is] maybe the most tangible example of systemic racism, where so many black families and other families were denied access to housing through practices such as redlining and we saw that created a huge gap in homeownership, which created then a huge wealth gap, which came with that. We believe we can do better than that as a nation and we see that housing certainly isn’t the only piece but it can be a critical foundation in a way that Habitat can be a part of the solution,” he said.

Pointing out Habitat for Humanity’s foundation as a faith-based organization, Reckford said: “We have a theological imperative … to put God’s love into action in a very tangible way to love our neighbors as ourselves and insist on reconciliation and relationship and justice.”

He explained how the organization began some 80 years ago out of an interracial farm just outside of Americus, Georgia.

“Some 80 years ago, there was an interracial farm, far ahead of its time where black and white farmers lived together, ate together, were paid equally and tried to create a community that was going to be a demonstration plot for the Kingdom of God of how communities should work. It was often at that time, as you can imagine, not welcome,” he said.

“We believe for our mission we have a business imperative. Our mission is to build homes, communities and hope but a key part of that has always been about breaking down barriers between people and building relationships. And in our image of our beloved community, it really will take everyone. And we know that housing is complicated and it’s going to take the public sector, the private sector and the social sector coming together. And we’ve got a lot of ideas of what has worked and what we believe can work,” Reckford continued.

“We are in the midst of our first U.S. advocacy campaign called Cost of Home, which is really to bring attention to the huge affordability gap for so many families and particularly families of color. And so we have a number of initiatives we are excited about to try to reduce that gap to increase access to homeownership, particularly for black families, and to increase homeownership more broadly as well as to broaden the supply that’s affordable for low- and moderate-income families. We believe that everyone benefits and the right model for any healthy community is to have a community where everyone can afford to live there and where people across income bands and certainly across race and other divisions can come together and live in the same community and build the kind of community we all want to be a part of.”