‘VeggieTales’ creator talks America’s sin of racism, conservative pushback, how Jesus would respond

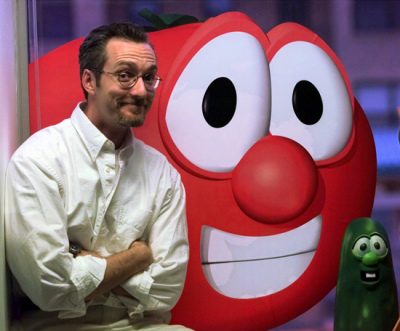

Phil Vischer, creator of the popular Christian animation "VeggieTales" and voice of Bob the Tomato, has been actively using his platform to address issues of racial injustice. The Christian Post spoke with the animator to discover his passion behind tackling these issues and his response to his conservative followers.

Following the police-involved death of George Floyd, many Americans are discussing issues pertaining to race and the debate around systemic institutionalized racism. To add to the discussion this month, Vischer first penned a blog, titled Racial Injustice has Benefited Me - A Confession, which he followed up with a video, “Race in America,” that's available on the Holy Post channel on YouTube.

Below is an edited transcript of Vischer’s conversation with The Christian Post (watch full video interview below) where he talks about why he, as a Christian, feels a responsibility to push back against racial injustice. He revealed some of the conversations he’s had with conservatives surrounding his stance and why he is willing to speak out whether people try and take it out on “Veggie Tales” or not.

Christian Post: Race is a topic you have discussed for some years now. Tell us what encouraged you now to share about how being white gave you access to opportunities that others did not have?

Vischer: Someone immediately said, “Oh, Phil, why weren't you talking about this two weeks ago?” And so I pointed them to the podcast we did three years ago and said, “I was all the way back.”

That started [because] my brother is the dean of a law school in Minneapolis, a Catholic University, St. Thomas University, after the Philando Castile shooting, which I believe was 2016 and led to quite a bit of protest. I-94 in Minneapolis, during the protests, was shut down, a group of protesters walked out onto the Interstate and shut it down. A lot of people in Minneapolis were very angry about that. It came out in the press that one of the leaders of that protest was an African-American woman, was a law professor who worked for my brother. Angry alumni demanded that my brother fire her for participating in that protest. He said he wasn't going to. And instead, he went back to them and said to these angry white alumni, “I want you to try to think of what it would take, what would have to happen in your life that would make you so upset that you would walk out onto an interstate and shut it down. What would it take for you to be that upset?”

My family started a Bible conference in northwest Iowa way back in the 1930s and it's still going on every year. My brother and I were supposed to teach a whole week class in 95% white, northwest Iowa and my brother decided to do a day on racial justice, on racial inequality. So he did a whole mess of research and then he did a day. We're talking about kind of hot button issues in our culture, but the data that he had come up with about racial inequality in America just blew my mind. So I came back to Chicago where we do the Holy Post Podcast, I mentioned on the podcast my brother taught this course, I just learned stuff, I had no idea. And people said, “Oh, tell us.” So I got my brother's notes and I presented them on the podcast as a special episode. That became one of the most popular episodes we'd ever done as lots of white Christians like me saud I'd never heard half of that stuff. So that was 2017.

Then we get to George Floyd in 2020. And Minneapolis, again, protests, again, shutting down interstates in Minneapolis again and then spreading all over the country. And I'm starting to see pop up all over social media: “Why are they so angry? Racism is done. Racism, we ended it in the 1960s.” And I started pointing people to that podcast episode to say this might help but it's an hour and 15 minutes long and you have to go 20 minutes in before it starts. So people just weren't doing it. I'm seeing all these little videos fly back and forth. Here's someone saying there's no such thing as racism. Here's two people arguing about white privilege. A lot of these videos just didn't have any data in them. They were opinions, but not history. So I thought, “OK, well, what if I took that podcast episode, that hour and 15-minute podcast episode, and tried to cram it down into a short as possible video as I could?” which turned out to be a 17-minute video to walk through 100 years of racial history in America. It turns out that just went absolutely viral. As of yesterday, it's been watched 5 million times.

CP: How did the information you learned turn from historical data to something where you thought you wanted to examine how racism has benefited you?

Vischer: The other part of the story is my family ... moved from Iowa to the suburbs of Chicago in 1980. I had a month left of middle school and then we started going to a church; it's in our denomination or local denominational church. ... My mother's been at that church without break for almost 40 years now. The church went through some really rough times, it was an aging white congregation and it was shrinking, just totally shrinking. And then we had no pastor and then it was getting smaller and smaller and it looked like we were kind of on death watch for our denomination. And our district superintendent in our denomination said, "Hey, I think you should talk. There's another church in the denomination right down the street that's growing that has a really dynamic young pastor. They don't have a building. You have a building, no pastor and you're shrinking. Maybe you guys should talk about merging." And we said, OK, what church is it? And it was a second generation immigrant Korean congregation. Wait, what? You want to take a mostly white congregation and an Asian immigrant congregation and just shove them together and hope that that works. We spent about a year meeting and discussing it. It's been four years ago now I was an elder at the time, both congregations voted and we decided to merge and create a multi-ethnic congregation.

So we have a Korean senior pastor, a Korean youth pastor, a Korean college pastor, a Filipino worship pastor, and then most of the rest of the staff is white from the old white church. And so we put all that together. But the amazing thing is, since we did that four years ago, the church has doubled in size. It's now about 1,000 people a week meeting, and it's African American, and it's Latino, and we have Indians. And we're getting like 120 college kids on a typical weekend because they want to worship someplace that looks like the world they're actually living in, that they're growing up in. Because of this, all of a sudden, I'm sitting around the fire in my small group with an African-American couple, listening to their stories of what it's like to live in white America, in the white suburbs. I'm talking with an Asian family about what it's like to be Asian in white America. I'm hearing stories that are just completely beyond my experience. That's what led me to start to look at my own story and the way I tell my own story, and that was the theme of that blog.

If you know my story, my dad walked out when I was nine years old, my parents split up and we went from upper middle class to probably for a couple years, we were living below the poverty line because my mother had never worked before. She had a nurse's degree but had never practiced. So she had to pull out the dusty nursing degree and try to find a job in Muscatine, Iowa, to support three kids after my dad had left. Then we relocated to the Chicago suburbs and we went to school and my brother went to Harvard and he became a successful college professor. And my sister has a doctorate and my mom got her doctorate and she became a college professor. So I used to tell the story like we had nothing, but we worked really hard and now look at us, what a success story!

Then I'm learning about, in particular, wealth inequality between African American families and white families, the average white family has 10 times the household wealth of the average black family. The average black family has 60% of the income of the average white family, but only 10% of the wealth. The reason that is because most wealth, most intergenerational wealth in America, is homeownership. That's how most Americans have generated wealth to pass from one generation to the next. We very actively, starting in the 1930s, encouraged white families to own homes and discouraged nonwhite families from owning homes. There were policies that we put in place and there were specific reasons which made sense at the time; now they look horribly racist. In hindsight, we declared that white and black families were incompatible racial groups and should never live in the same community; that was in 1932 in the Federal Housing Administration guidebook ... It was policy. Because of that, so few African-American families have homes that they've owned that have been passed through generations that have generated wealth for college, in particular wealth for how do you move and start your life over if your life falls apart? I realized that when our lives fell apart in Muscatine, Iowa, and we had nothing, we didn't have nothing. We had a nice house for Muscatine, Iowa, standards and my mom was able to sell that house and use the money to buy a much smaller house but in a nice suburb of Chicago, which had funded, by all those nice houses, fantastic schools.

CP: There are people debunking that systemic racism exists. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Vischer: There's a pretty good argument to say there aren't. It is very hard to find explicitly racist laws today because it's illegal. So even if they pop up somewhere, pretty soon somebody's going to notice and file a lawsuit, and they're knocked down. But that doesn't mean that there isn't residual racism from prior laws. So just for example, do you know why there's no unemployment insurance for agricultural workers? Because in the 1930s, during the Depression, when unemployment insurance was proposed, Southern senators insisted that it be for white people only, that no black people could get unemployment insurance. Northern senators said, “No, we're not doing that.” But they had to come up with a compromise. The compromise was it doesn't apply to agricultural workers or service workers, which in the South were the jobs held by black people. So it was the same thing, it was the same result. It's not an explicitly racist law but it was done in a way that had the same impact. We see that over and over again. There were whites-only zoning ordinances in suburbs where if you were a nonwhite family, it was against the realtor’s code of ethics to show a house in a white neighborhood to a nonwhite family. You would lose your realtor's license until 1950, if you help the black family buy a house in a white neighborhood. The realtor’s code of ethics is a system, so that's not an individual sin. That's a systemic sin.

We forget that the Bible has both. The Bible, we always talk about that we're called to repent as individuals of our individual sins. But Israel over and over again is called to repent as a nation for things that not every member of the nation did. After the exile, they come back and they start intermarrying with people from other nations that was against God's law. They're called to repent. Did every single Israelite intermarry with another nation with a woman from another nation? Of course not. But the whole nation is called to repentance. We're so individualistic in America that we can't stand the notion of being held responsible for anything that we didn't individually do. So we focus on the New Testament, which is a much more individualistic focus because it's not about a nation. It's about individuals within the Roman Empire. If you go back to the Old Testament, you see the people of God time and time again called to repent for things they did collectively as a nation, not individually.

I think that's a moment we in the Church, as the people of God say, “OK, no, you personally never owned slaves, you personally never kicked African Americans out of your coffee shop, you personally did not redline your neighborhood so that African Americans couldn't get subsidized mortgages. But we collectively [did].” We're so quick to say, “We won World War II, we won the Cold War, we sent a man to the moon.” No, you didn't do any of those things but America did those things. And we love to put ourselves together when it's something good. Then you say we oppress the Native Americans; "I didn't do that." So we clearly have a double standard where we love to associate ourselves with the great things America has done and hate to be associated with the terrible things America has done.

America is no better or worse than we are. We all do good and terrible things. So some of the pushback for me has been, “You're making America sound terrible and that really makes me sad.” America is no nobler nor sinful than we are, it is the sum of us. So unless you reject the idea that you are sinful, you can't reject the idea that America is sinful. And we need to repent of those sins.

CP: Many conservative readers are pushing back saying, "The gospel is all that we need" and saying statements such as what you’ve shared are “liberal.” What do you say to that?

Vischer: It's funny and this is a little controversial to say, but it's true. We never say the Gospel is all we need when we talk about abortion. We say we need conservative Supreme Court justices, and we need to change laws and we need new guidelines, and we need new policies. Somehow, when we turn the page to racism, now the Gospel is all we need and we don't need any laws. We don't need to do anything to change. Nothing needs to change in society except the heart. So I find it a little funny when we're picking the issues that we personally care about and saying, "We really need to be active, we need to go out, we need to go out and protest abortion," and we do, I'm with you. Let's go out and protest abortion.

But then to say, "Oh, wait, the thing you want to protest? No, no, the Gospel is all we need." Let's take a step back and examine that. I think we might have a double standard there. So I think God cares about both. I think He cares about the unborn. I think He cares about the newborn black boy in the inner city who has a one in four chance of ending up in prison in his lifetime, who is more likely to go to prison than to go to college. I think that breaks God's heart also.

I've had people push back and say, "Well, rank them, rank abortion versus racism. I don't think God has a big wall chart of sin. So we can walk and chew gum at the same time. We can be pro-life and pro-our black friends at the same time. We can be anti-racist and anti-abortion at the same time. Our politics make it difficult. We've taken all of these issues and we've divided them between two buckets: the liberal bucket and the conservative bucket. And if you identify yourself as a conservative, you can't care about anything that the liberals care about. And if you identify yourself as a liberal, you can't care about anything that is conservative. That's ridiculous.

As Christians, here's what that means. It means we've made our political identity more important than our spiritual identity. Because Jesus is never going to say, "I would care about that issue, except I hear liberals care about that issue, or I would care about that issue, except I hear Republicans care about that issue so I'm not going to care about that issue." No! Jesus' heart went out to the least of these. And the least of these is the unborn, the least of these are African Americans in the inner city who don't have a chance to get a good job, who can't find fresh food within a five-mile radius, who will be discriminated against in housing practices.

We've seen recently when an African-American woman applies for an apartment in New York City, she's more likely to get the apartment if she has an Asian roommate, and the Asian roommate puts her name on the application instead of the African American's name. There's no law that says African-American women can't rent apartments. But you're more likely to get a note back saying the apartment's no longer available if your name sounds African American. We can be upset about that without it meaning we're somehow betraying our tribe because our tribe is Christ followers. It's not Democrats. It's not Republicans. It's Christ followers and He cares about everybody.

CP: How can we encourage people to stop being offended with what's happening right now and actually deal with their own biases?

Vischer: I go back to what my brother said to his angry alumni. When they said, "You need to fire that woman because she shut down I-94" and he said, "I want you to tell me what would make you so upset that you would do what she just did?" Just think about that.

So for every white Christian out there — whether you consider yourself liberal, conservative, libertarian, moderate, independent, I don't even care – what could happen that would make you so upset that you would go out and protest like that, that you might even feel like picking up a rock and throwing it through a window. If you say, "I would never ever do that because that's not American. We kind of have to remember that's how America started. It started as a protest with people in the middle of the night, picking up boxes of tea and throwing them violently off the ship in protest. Then OK, are you a Protestant? What does that word mean? What's the root of Protestant? It's protest. We all started out as protesters. You're American, you're a protester. You're a Protestant, you're a protester. So we're all protesters!

What we don't like is when people protest against things that we're not that upset about. Then we get kind of bent out of shape and we really don't like property damage. That's understandable. There are people all over the world that are being persecuted in ways that are real and violent and bloody, and way worse than losing your favorite Arby's. So it's OK, they had insurance, they can build a new Arby's. Stop staring at what's happened and look at the issues behind. Ask the question, what would make you so upset that you would be willing to do that?

We did a whole podcast episode about the Christian tendency to enjoy conspiracy theories. Just like the people with the coronavirus who say “Bill Gates did it …,” conservative Christians have a high proclivity to buy into some of those stories, partly because we believe the world is actually against us, which is biblical. There is some biblical basis in that partly because of the history of the 20th century and starting with the Scopes Monkey Trial and the history of fundamentalist Christianity. We felt that American media and the American intelligentsia, the "elites" turned on us. Right about in 1920s to 1930s, we believe that America turned on us and we pulled back, we became more insular, and we became more angry and more suspicious. That's gone on ever since.

So when we hear. "I heard that Bill Gates is trying to take over the world and put microchips in all of our children. And that's probably the mark of the beast. That makes sense to me." So now it's the same thing when we see a riot. When we see a race riot and we hear, "I heard that George Soros funded that riot. That makes sense, that a rich guy who's on the other side politically is behind all this."

We just have to calm the heck down because the other side will do it to us too. I don't know if you've ever watched any episodes of "The Handmaid's Tale" on Hulu. There are people on the far left that believe that is what I want because I'm a conservative Christian, that I want America to look like "The Handmaid's Tale." So Handmaid's Tale is a conspiracy theory about conservative Christians and that's what we would do. And you can find somewhere online, a sermon from some preacher somewhere that will support that suspicion. So we do it to them and they do it to us. We find some radical voice on the left and say, "Aha, they want to ban the Bible. They want to get rid of all white depictions of Jesus."

CP: How do we keep the heart of Jesus in this, when such extreme thoughts are prevalent?

Vischer: I don't think Jesus ever looked at a stranger and assumed the worst about them. Ever! I think He always assumed the best. The story of the Good Samaritan, it literally is a story of your enemy, the person you despise, being the one who helps you, being the one who loves you. So when He's telling a story like that, He's just not letting you have prejudice against your enemy. He's not letting you think the worst, assume the worst. When we assume the worst, we're going against the teaching of Christ. So when I look at my enemy and I see him as my brother and say, "How can I show this person love? But I think he's trying to ruin America." Honestly, that is not my number one priority as a follower of Jesus, to worry about who is or isn't more likely to ruin America. My number one priority as a follower of Jesus is to show him the love of Jesus. That's it. And then we'll take it from there and we'll probably become friends.

CP: Have you been afraid that people are going to take this out on "VeggieTales"?

Vischer: "VeggieTales" is now owned by NBC Universal, which is a big giant media company and they did a deal with the Trinity Broadcasting Network to create some new episodes which I've been involved in. I need to do what I believe God has called me to do, regardless. Actually I had someone say, "Man I really love VeggieTales but I'm so sorry that you're a leftist now." If loving my neighbor means you can't like VeggieTales anymore, first of all, I'm not sure you watched episode number three, which was are you my neighbor? It was about loving the weirdos and the people that are different. So it's OK. I'll keep making veggies as long as they invite me to and I'll keep talking about interesting things.

We are in such a crucial moment where our culture is becoming increasingly post-Christian. That makes us very uncomfortable because it is very new. We are not used to being a minority and we don't know what to do with that and it's very easy to just default to anger because that's the human response to a loss of privilege, or a loss of power, or a loss of influence, is to fight back. This is a perfect opportunity to go back to the way the Church was in the first, second, and third century and say, "Well, gee, they had zero influence. They had zero political power." What do they do? They loved people. They love people and it changed the Roman Empire. It absolutely transformed the Roman Empire. So we need to think of ourselves a little more like that, that we're not living in the promised land. We're living in the Roman Empire where we are exiles and we are influenced by love, not by anger.

CP: Is there anything else you'd like to add?

Vischer: I don't think so. The Holy Post Podcast. You can check it out. We talk about stuff like this every week. It gets pretty interesting. And we'll keep doing what we're doing.