'Saved'? 'Converted'? For Evangelical media, them's fightin' words

For whatever reason, Evangelicals love this one quote from Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan Order, which goes something like this: “Preach the Gospel. If necessary, use words.”

Even as a newborn believer in Christ, I never understood why anyone, pastor or layman, wouldn’t want to use language to convey the glory of God, His Word and His salvation.

Who would ever suggest such a thing?

Actually, technically, no one. Because Francis of Assisi never said it.

It’s actually a poorly paraphrased rendering of his Rule of 1221, which quotes none other than the Apostle Paul, who wrote, “Let us love not with word and mouth, but in deed and in truth.”

Turns out a fabricated quote about words and the Gospel might as well have been a prophetic utterance concerning one of the workshops at the Evangelical Press Association’s 2024 Christian Media Convention.

Created in 1948, the Evangelical Press Association is the world’s largest professional organization of Christian print and digital publications, from magazines and newspapers to newsletters and content-driven websites.

Every year, the EPA holds its annual convention where journalists, photographers and other media creators gather to network, to learn, and, not unlike most other church gatherings, to feast.

It’s where publications are honored for their work in various media categories, not as the world honors, not like the Golden Globes or something glitzy, but as servants in the work of the Gospel, as co-laborers with Christ. As light and salt in an age of darkness and corruption.

Or so we tell ourselves.

Amid a dizzying barrage of workshops and meet-and-greets, there was one offering that, at least for me, raised questions as to exactly what was being accomplished at such a gathering, particularly where newbies and aspiring journalists pay good money to attend in the hopes of landing their next gig.

Case in point: the “Communicating Words and Visuals with Inclusivity” workshop from World Vision magazine editor-in-chief Kristy Glaspie, whose presentation looked at ways on how journalists can, as the workshop description stated, “eliminate words and images that subconsciously — or consciously, in some cases — create an ‘us vs. them’ mindset that places our work and goals in a position of a savior or rescuer mentality.”

It was this “savior mentality,” in fact, which, we were told, World Vision, as a matter of policy, actively seeks to avoid by eliminating the use of specific verbiage in its reporting — including words that directly or indirectly relate to the Gospel message itself.

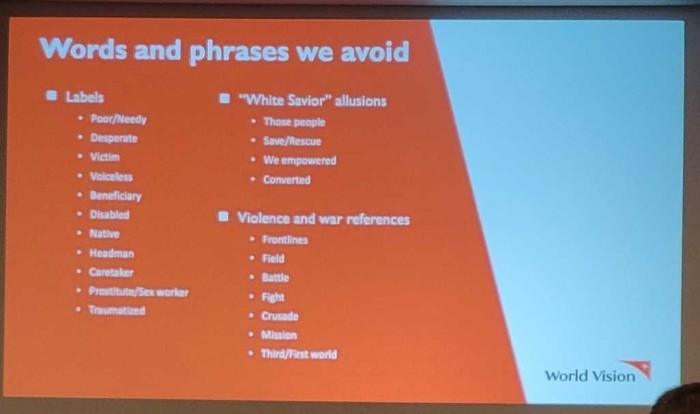

Glaspie unveiled a slide featuring the World Vision logo and titled “Words and phrases we avoid,” a list which included nearly two dozen items which any Christian missionary worth his calling would be hard-pressed to avoid.

The list included "labels" such as "poor/needy," "desperate," "voiceless," "native," "prostitute/sex worker" and "traumatized."

Under the list "Violence and war references," a number of theologically-charged words were listed: "field," "mission," "battle," "fight," "crusade" and "third/first world."

But it was the grouping titled "White Savior allusions" that was perhaps the most revealing about World Vision's editorial worldview, with phrases like “save/rescue” and “converted.”

“We are very intentional. We are not saving or rescuing anybody, God does all the saving or rescuing,” said Glaspie. “We don’t want to ever imply that we’re the ones doing things.”

While I was certain no one in that room believed themselves — and not Jesus of Nazareth — to be the Savior of the world, my theological "Spidey sense" had already started tingling.

Glaspie went on to offer an explanation for including the word “converted” — a word used by both Jesus and His apostles throughout the New Testament — on the list of banned phrases.

“Oftentimes, because we work in so many different cultures around the world, we work in a lot of places where Christianity is either not allowed or the Christian population is less than two percent,” she explained. “We are very sensitive to accusations of proselytization, and so, none of our work is conditional on people becoming Christians. None of our work is conditional, [like] ‘Come listen to a Sunday School lesson.

“We will help anybody and everybody, regardless of their faith. That’s really important. So we never use the word ‘converted’ ...”

In fact, Glaspie explained, the reasoning behind such a strategy was best illustrated two years ago during a World Vision clean water effort in Ethiopia, where she said “hundreds of people” came to faith in Christ without any Gospel presentation.

“We did the work, we didn’t even do any of our Christian witness work in the community, and hundreds of people came to know Jesus, because they’re like, ‘Why are you doing this for us?’ ... We like to do the work to prompt the question.”

When I pressed Glaspie further about a policy that some could view as restricting Gospel-adjacent language, she explained that with some 53 denominations represented at World Vision, their goal is to “use language that is going to be most appealing to most Christians.”

“I think it’s one thing to use terminology that Scripture uses, but I think the question to ask is, ‘How are we using it?’ We’re saying, ‘we’re saving people,’ are we saving people?” she explained. “We see in Scripture that every person plays the role in anybody coming to choose to follow Christ.

“So I might maintain that maybe you might be the last person in the line that, you know, has the conversation with them, and they decide to give their life to Christ, but you, in having that conversation, are not saving them. It’s been a long line of people planting seeds along the way.”

When pressed on whether those restrictions might inhibit the way journalists communicate the message of Christ and Him crucified, Glaspie said it all depends on the intent behind the language.

“... I think you can still use those words, but being intentional about how are we using those words and are we assigning more value to us in our role in the work versus God and His role in the work?” she said.

There we were, at an Evangelical media workshop, Christian journalists being told not to evangelize others for fear of causing offense. That the words of the Gospel aren’t “inclusive” enough for the mission field.

And we wonder why the mission and the message of the Church is weak in America.

And we hand-wring over falling attendance numbers and apostasy.

And we scratch our heads when we’re told that Gen Z wants nothing to do with Evangelicalism.

We’re too busy telling our own not to use the words of Scripture and, yes, to proclaim salvation to the lost and the Savior to a dying world.

In response to a request for comment on the "Communicating Words and Visuals with Inclusivity” workshop, the EPA Executive Director Lamar Keener said the organization “does not make endorsements.”

Fair enough, but I couldn’t help but wonder what James DeForest Murch would say.

Murch, who founded the first EPA convention in Chicago over 75 years ago, led an effort to define the mission of the EPA to “promote the cause of Evangelical Christianity” and “enhance the influence of Christian journalism” through “Christian fellowship among members of the Association.”

What would Murch say if he knew that his organization — which now boasts over 300 members representing a combined readership of more than 20 million and has the word “Evangelical” in its masthead — would one day offer a workshop in which journalists would be told not to engage in evangelism?

The fact is, that language is foundational to the Good News of Jesus Christ. In the beginning was the Word, the logos, the Divine Expression.

"And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us." He became One of us, the Man of perfection mingling with the lot of sinners. He taught us language is indeed everything, that it’s not what goes into the mouth that defiles, but what comes out of it.

He used the very language which World Vision now tells us is insensitive and potentially offensive.

Jesus said, “Unless you are converted and become like children, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3).

In John 4:35, the Messiah tells us, “Do you not say, ‘There are still four months until the harvest’? I tell you, lift up your eyes and look at the fields, for they are ripe for harvest” — a verse custom-made to inspire the most weary of missionaries.

Romans 10:9 says, “If you declare with your mouth, 'Jesus is Lord,' and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.”

Paul tells us to “fight the good fight of faith.”

All of these words, says World Vision, are words we as Christians are free to believe but must not say.

These are all biblical terms, inspired, as Evangelicals believe, by the Holy Spirit, to describe big-ticket theological concepts such as justification by faith, regeneration, and, yes, conversion.

Why, then, are we teaching the next generation of Christian journalists to bite their tongue? To watch what they say?

Are we not training them to self-censor at the behest of a dying world that would like nothing more than for Christian media to just shut up already about our King?

The first thing we learn as journalists is that accuracy matters. Words matter.

And I, for one, refuse to mince words when it comes to getting His Word right.

And you can quote me on that.

Ian M. Giatti is a reporter for The Christian Post and author of the upcoming THE ASSEMBLY OF JACOB + THE KINGDOM OF YAHWEH. He can be reached at: [email protected].